Elvis on Tour is a 1972 American concert film starring Elvis Presley during his fifteen-city spring tour earlier that year. It is written, produced, directed by Pierre Adidge and Robert Abel and released by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM).

| Elvis on Tour | |

|---|---|

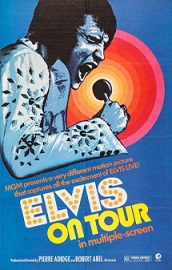

Poster for the theatrical release, 1972 | |

| Directed by |

|

| Written by |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | Elvis Presley |

| Cinematography | Robert C. Thomas |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Elvis Presley |

| Distributed by | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer |

Release date |

|

Running time | 89 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | US$1.6 million |

Following his return to live performances and touring after his acting career, Presley starred in the documentary Elvis: That's the Way It Is with MGM in 1970. Presley's manager, Colonel Tom Parker, then arranged a deal for another documentary film with the studio by early 1972. MGM hired Abel and Adidge, who previously documented Joe Cocker's 1970 tour of the United States. The crew filmed four Presley shows that were later intertwined with interviews. Assisted by Martin Scorsese, it featured the use of split screens.

The film was released on November 1, 1972. While it opened to mixed reviews, it became a box-office success. In 1973, Elvis on Tour won the award for Best Documentary Film at the 30th Golden Globe Awards.

Background

editAfter an eight-year hiatus where he focused on his acting career, Elvis Presley returned to live performances with his 1968 television special, Elvis.[2] With the success of the show, his manager, Colonel Tom Parker, arranged a residency for Presley at the International Hotel in Las Vegas, Nevada, in 1969. Presley assembled a new band comprising James Burton (guitar), John Wilkinson (rhythm guitar), Jerry Scheff (bass guitar), Ronnie Tutt (drums), Larry Muhoberac, (piano) and Charlie Hodge (rhythm guitar, background vocals). The backing vocals of The Sweet Inspirations, The Imperials, The Stamps, and Kathy Westmoreland accompanied the band.[3] Additionally, the 30-piece Joe Guercio Orchestra accompanied him.[4]

Presley made his first appearance outside Las Vegas at the 1970 Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo, where he performed between February 27 and March 1, 1970. Parker then made a deal with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) for a concert film shot in August 1970 during the Elvis Summer Festival event at the International Hotel in Las Vegas.[5] Presley began touring the United States again in 1970 after a thirteen-year hiatus.[6] He began his tour schedule with an appearance at the Arizona Veterans Memorial Coliseum in Phoenix, Arizona, on September 9, 1970. In November 1970, as Presley toured, MGM released the concert film now entitled Elvis: That's the Way It Is.[5]

The release of the soundtrack of That's the Way It Is reached number 21 on Billboard's Pop Albums chart. Meanwhile, the release of Elvis Country (I'm 10,000 Years Old) in early 1971 peaked at numbers 12 and 6 on the Pop Albums chart and Top Country Albums chart, respectively.[7][8] A soundtrack was not issued for this film, likely because of the recent release of As Recorded at Madison Square Garden (1972) and upcoming release of Aloha from Hawaii via Satellite, both live albums. Various releases, including two box sets (one by RCA/Legacy and the other by RCA's Elvis Presley collectors' label Follow That Dream Records, or FTD), finally occurred in 2022, 2023, and 2024 to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the film and the concerts and rehearsals recorded for it.

Cast

edit- Elvis Presley as Self

- Charlie Hodge as himself, Elvis' friend and vocalist/acoustic rhythm guitarist[3]

- James Burton as himself, lead guitarist for Elvis Presley's TCB Band[3]

- John Wilkinson as himself, TCB Band (electric) rhythm guitarist[3]

- Jerry Scheff as himself, TCB Band bassist[3]

- Glen D. Hardin as himself, TCB Band pianist[3]

- Ronnie Tutt as himself, TCB Band drummer[3]

- Estelle Brown, Sylvia Shemwell, and Myrna Smith as themselves, members of The Sweet Inspirations and backing vocalists for Elvis Presley[3]

- J.D. Sumner, Donnie Sumner, Bill Baize, Ed Enoch, and Richard Sterban as themselves, members of J.D. Sumner and The Stamps Quartet and backing vocalists for Elvis Presley[3]

- Kathy Westmoreland as herself, soprano backing vocalist for Elvis Presley[3]

- The Joe Guercio Orchestra[4]

Production

editIn early 1972, Parker and MGM began the negotiation process for a new documentary film to be shot in Las Vegas. The project, originally titled Standing Room Only, was planned to be released with its respective soundtrack album. MGM agreed to pay Parker and Presley $250,000 (equivalent to $1,821,000 in 2023). Following the terms of the new contract signed between the singer and his manager in February 1971, Presley received two-thirds of the income generated by his appearances, while Parker received one-third.[9]

The concept of the film was changed to show Presley as he toured arenas throughout the United States.[10] Presley would appear in fifteen cities during his spring tour.[11] For the tour, concert promoters paid Presley's usual fee of $1 million (equivalent to $7.28 million in 2023).[9] Jack Haley Jr., then vice president of MGM, approached Robert Abel and Pierre Adidge. Abel and Adidge had worked previously on the documentary Mad Dogs & Englishmen that followed Joe Cocker's 1970 tour of the United States. After his experience with Cocker, Abel expressed his disinterest, but Adidge convinced him to travel to Las Vegas to see Presley in concert.[12] After the show, the two met the singer backstage. Presley convinced the still reluctant filmmakers to take on the project. The directors told Presley that they did not like Elvis: That's the Way It Is, as they felt he was acting for the cameras. They warned Presley they would only work on the project if he acted naturally; Presley agreed he would.[13]

Adidge and Parker visited the tour locations while Abel made arrangements for the equipment and crew. The directors planned to use small, unobtrusive cameras. They would edit the footage later to increase the image resolution to that of a 70 mm film.[14] Upon meeting Presley, Pierre and Abel felt he was too bloated and pale. They worked with the lighting to hide Presley's appearance.[13] The team had eleven Eclair cameras equipped with eleven-minute film rolls. To avoid loss of continuity, the cameras were cued to a tape deck that collected the video and sound from all the sources.[14] In March 1972, Presley traveled to Los Angeles for rehearsal filming on March 30.[15] For the sessions at RCA Records's Hollywood studio, Presley sang the numbers he prepared for the tour and performed Gospel jam sessions with the musicians.[16][17]

Abel attended the start of Presley's tour in Buffalo, New York, on April 5, 1972. He taped the concert with a simple camera to study Presley's performance later.[14] The Associated Press reported the show broke the Buffalo Memorial Auditorium's attendance record for concerts with a crowd of 17,360.[18] The crew began shooting the documentary at Presley's appearance at Hampton Roads, Virginia.[14] the Daily Press reported the show on April 9 at the Hampton Coliseum, had a sold-out crowd of 22,000. There were traffic jams on Interstate 64 an hour before the show.[19] The newspaper described the audience welcoming Presley with "deafening applause and screams". It remarked that the singer was "a little chubbier than he used to be" but that "the electricity" of his performance was as "magnetic as ever".[20] The crew filmed Presley's performance the following night in Richmond.[14]

After the Richmond show, Abel returned to California to review the film and work out the structure of the documentary.[14] He joined the team for Presley's performance in Greensboro, North Carolina, and showed Parker the footage they had at a local theater. Presley's manager reacted positively.[21] Aididge's crew shot Presley behind the scenes in Jacksonville, Florida, where they captured what would become the documentary's final scene.[14] The crew recorded a fourth concert at Presley's show in San Antonio, Texas.[14] The San Antonio Express estimated 10,500 concertgoers attended the show, and reviewer Bill Graham noted the audience was "deafening" when Presley came on stage. The piece stated that Presley's "sound hadn't changed" and that he "was at his best, if not better than ever in his entertainment career". The reviewer noted there were more males in the crowd compared to the 1950s and that the audience "had matured". Graham commented the younger fans "seemed to sit and cheer in awe", and though "there wasn't a mad rush for the stage", Presley "made his now famous rush for the waiting car".[22] After two full weeks of shooting, the production team finished the photography.[14] The team told the Copley News Service they shot 60 hours of footage.[23]

Through Presley's friend, Jerry Schilling, the directors convinced the singer to use footage of his early career that included his appearances on The Ed Sullivan Show.[24] A fan club in England provided additional early footage.[10] Parker opposed references to Presley's early career, as he felt it would portray the singer as a "nostalgia act". Schilling convinced Presley to allow the filmmakers to interview him at the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studios.[24] The interview provided the film's narrative, as the voice clips were used between performance sequences as the tour progressed.[17] Presley's father, Vernon, was interviewed at Graceland.[10] The release of a companion live album was canceled after an overcurrent damaged the recording equipment on the fourth night of the tour.[25] The costs of shooting the film amounted to $600,000 (equivalent to $4,370,400 in 2023). [26] With Presley's performance fee, the total production cost $1.6 million (equivalent to $11,654,400 in 2023).[27]

Parker asked MGM to remove parts of Presley's interview from the film, including the singer's negative comments about his acting career.[28] Some of his comments were ultimately included in the final cut with a compilation film clip of Presley's on-screen kisses that reflected the repetitive plot of his films.[29] Ken Zemke was the documentary's primary editor,[10] while Martin Scorsese edited the film's montage. As in Woodstock, Scorsese used split screens to focus on the performer, as well as on individual band members.[30] Abel's company, Cinema Associates, partnered with Cinema Research Corporation to develop a technique to change the film's resolution: the footage was originally shot in 16 mm, and it was later squeezed or compressed to a 35 mm film that gave the material a quality gain of 50%. The transfer was then augmented to 70mm with the use of an optical printer. Abel also used the technique for the production of his 1973 film Let the Good Times Roll featuring footage of singers from the 1950s and 60s.[31]

Release and reception

editElvis on Tour was released on November 1, 1972.[32] As Parker closed negotiations with NBC for Presley's upcoming television special Aloha from Hawaii via Satellite, MGM executive James T. Aubrey urged them to delay the broadcast planned for November 18 to avoid both releases overlapping.[33] Elvis on Tour placed at number 13 on Variety's National Box Office Survey.[27] The film covered its production expenses soon after its opening,[27] as it was shown in 187 theaters in 101 towns and took in $494,270 in three days.[34]

The January 1973 opening of the documentary in Japan attracted 52,830 spectators who contributed $131,311 to the local box-office.[35] On January 28, 1973, Elvis on Tour tied with Walls of Fire for Best Documentary Film at the 30th Golden Globe Awards.[36] It became the only film starring Presley to earn an award.[32]

Domestic critical reception

editThe Los Angeles Times felt the documentary was "unpretentious", while the piece favored it over Elvis: That's The Way It Is. They preferred the atmosphere of the tour compared to Presley's Las Vegas performances, as the critic noted that Presley appeared "assured, relaxed". The article closed by describing Presley as "an American institution" and the film as "highly enjoyable".[37] The New York Times' Vincent Canby opined that Presley's shows were "okay", while the scenes that showed him moving from venue to venue were uninteresting. Canby remarked that the film "remained unconvincing", as he suggested that the documentary portrayed Presley as he appeared in the Hal Wallis films he starred in instead of showing his private persona. The critic considered that "there is no 'real' Elvis left", as he closed the review suggesting that the documentary "sanctified him".[38] Meanwhile, for Rolling Stone it was "the first Elvis Presley" movie, as the publication compared it with the content of his previous releases.[26]

The Boston Globe felt Elvis On Tour was made "four rock documentaries too late". The reviewer favored Presley's live sets, but he felt the scenes that followed him to the next show were repetitive and that Presley played for "idolatrous legions". The gospel rehearsals were praised in contrast to the transitional travelling scenes. Meanwhile, the inclusion of footage from The Ed Sullivan Show was welcomed. The reviewer remarked Parker's discrete appearance on the documentary and he praised the cinematography.[39] The San Francisco Examiner opined that the film expanded upon Elvis: That's The Way It Is, as the newspaper called it "beautifully done" and "absorbing and fascinating". The reviewer felt that the documentary presented redundant scenes as Presley moved along concerts, and that his changes of costumes and "the signs of fatigue on his face" differentiated the concerts. The article determined that Presley "comes through magnificently", while Adidge and Abel were praised for their use of split screens and speed techniques that were "used with taste". The soundtrack was deemed to be "generally excellent".[40]

The Atlanta Constitution opened its review calling Elvis On Tour "disappointing". Critic Howell Raines pointed out that Adidge and Abel failed to present Presley's "appeal as a performer". Raines lamented the end result, as he felt that the film did not reflect Presley's "eminence in entertainment history" and that the footage of the concerts omitted Presley's choreography.[41] For The Courier-Journal, critic Billy Reed deplored Presley's previous films, while he remarked that Elvis On Tour cast Presley "in a role that truly only he can play. Elvis is himself." Reed considered the documentary "worthwhile", noting its "excellent close-up, split screen photography".[42]

The St. Louis Post-Dispatch said Presley's fans would enjoy the film but that others would "enjoy the handsome production for a while", but that they would be then deterred by "the repetitious visuals and hope that the tour comes to an end". The reviewer praised Zemke's work editing the film, but he felt that the use of the split screens "becomes too much". The newspaper noted Presley's offstage presence marked by "warmth and grace" and that the performances onstage were "excellent". The piece criticized the scenes that showed Presley between shows and the segment filmed at Graceland.[43]

International critical reception

editIn Canada, The Gazette hailed Elvis On Tour, for showing Presley's "power and glory". Reviewer Dane Lanken felt that while the cinéma vérité camera work was "extreme" the performance of Presley "comes through". Lanken attributed Presley's success to his voice. The review praised the musicians and backup singers, but noted that the documentary did not offer personal details of Presley nor of his manager.[44] Meanwhile, the Windsor Star considered Parker "an old foxy carnival barker" who "pulled another fast one". The newspaper deemed it an advertisement and the reviewer felt that it was the same film as Elvis: That's The Way It Is. He called both films "pseudo-documentaries" that did not show Presley off-stage and instead focused on his show. The reviewer welcomed Presley's performance of Gospel numbers, but lamented the singer's large entourage and choice of attire. It concluded that Presley and Parker's talent could "be seen in ultra extravagance" on the film.[45] For The StarPhoenix it was a "visual treat" that it compared to a television special. The review praised the work by the backup singers and Presley as he "cling(s) to the gospel songs in a reassuring manner".[46] The Richmond Review perceived Elvis On Tour as "another quicknik vehicle" for "keeping" Presley's "face in front of his North American audience". The review delivered a negative reception of the use of split screens as "annoyingly amateurish" and determined that the film's target audience was Presley's fanatics.[47]

In England, The Guardian concluded there was a "good use of the split screen", there were "plenty of numbers for the fans" but said that Presley's "mystique remains unexplored".[48] The Evening Standard called it a "disappointing round of concert platforms". The review concluded that with the similarity of the cities and venues, the production team could "have shot it all in one spot". It favored the montage of Presley's movie kisses, but it dismissed the documentary as "a PR handout".[49] For The Observer, critic George Melly called Presley "a survivor of the early days of rock 'n' roll" and "the silent majority's superstud". The critic added that the reaction of the fans to Presley offered "a certain awareness of the absurdity". The piece concluded "his batman costumes" were "really splendid".[50]

In Australia, The Sydney Morning Herald received the documentary as "fairly cynical". The reviewer stated that "disappointingly" with the concert and backstage footage did not reveal the private life of the singer. They concluded that Presley was "singing as well as ever" and that the split screens were "well used".[51] Meanwhile, The Age pointed the heavy use of split screens and that Presley performed "through scores of indistinguishable pops". The piece concluded the film "grows repetitive to the unconverted."[52]

Legacy

editElvis On Tour was first broadcast on television by NBC, on January 15, 1976.[53] Outtake footage from the film was used for the 1981 documentary This Is Elvis.[54] MGM released Elvis On Tour on VHS in 1982.[55] In 1997, a new VHS version was released. The new edition received negative criticism for the removal of the split screen footage.[56] In 2003, the show recorded in San Antonio, Texas was released with the compilation Elvis: Close Up.[57] In 2004, Elvis on Tour – The Rehearsals was released by Presley's official collector label Follow That Dream.[58]

In 2010, Warner Bros. via Turner Entertainment released the film on DVD, Blu-ray, and digital video.[1] As the release matched Presley's 75th birthday, the film was later screened during the annual Elvis Week in August 2010 in Memphis, Tennessee,[59] as well as in 460 theaters across the United States.[60] The re-release grossed $587,818 at the box office.[61] The new version replaced the original use of Chuck Berry's "Johnny B. Goode" on the opening credits with "Don't Be Cruel" due to copyright issues.[56] The Wall Street Journal deemed it "an unfettered and revealing look at Presley's rich gospel side, his sizzling performing power and popularity, and even his ongoing battle with stage fright".[62]

References

edit- ^ a b Turner Entertainment staff 2010.

- ^ Guralnick, Peter 1999, p. 293.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Eder, Mike 2013, p. 173.

- ^ a b Billboard staff 1970, p. 41.

- ^ a b Guralnick, Peter 1999, p. 375.

- ^ Wolff, Kurt 2000, p. 283.

- ^ Billboard staff 2021.

- ^ AllMusic staff 2011.

- ^ a b Guralnick, Peter 1999, p. 459.

- ^ a b c d Slaughter, Todd & Nixon, Anne 2014, p. 104.

- ^ Doll, Susan 2016, p. 206.

- ^ Guralnick, Peter 1999, p. 462.

- ^ a b Guralnick, Peter 1999, p. 463.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Guralnick, Peter 1999, p. 464.

- ^ Guralnick, Peter 1999, p. 460.

- ^ Guralnick, Peter 1999, p. 461.

- ^ a b Eder, Mike 2013, p. 309.

- ^ AP staff 1972, p. 11-A.

- ^ Edgar, Henry 1972, p. 3.

- ^ Edgar, Henry 2 1972, p. 10.

- ^ Guralnick, Peter 1999, p. 465.

- ^ Graham, Bill 1972, p. 14-A.

- ^ Anderson, Nancy 1972, p. 10.

- ^ a b Guralnick, Peter 1999, p. 466.

- ^ Crouch, Kevin & Crouch, Tanja 2012, p. 133.

- ^ a b Hopkins, Jerry 2014, p. 335.

- ^ a b c Doll, Susan 2009, p. 228.

- ^ Williamson, Joel 2014, p. 257.

- ^ Victor, Adam 2008, p. 134.

- ^ Baker, Aron 2021, p. 257.

- ^ Harris, Winifred 1973, p. 1471.

- ^ a b Jeansonn, Glenn, Luhrssen, David & Sokolovic, Dan 2011, p. 190.

- ^ Guralnick, Peter 1999, p. 479.

- ^ AP staff 2 1972, p. 8.

- ^ Glover, William 1973, p. 14 – Part IV.

- ^ AP staff 1973, p. 6.

- ^ Thomas, Kevin 1973, p. 10 – Part IV.

- ^ Canby, Vincent 1973, p. 3 – section 2.

- ^ Santosuosso, Ernie 1972, p. 48.

- ^ Elwood, Phillip 1972, p. 30.

- ^ Raines, Howell 1972, p. 10-B.

- ^ Reed, Billy 1972, p. A14.

- ^ Pollack, Joe 1972, p. 2D.

- ^ Lenken, Dane 1972, p. 46.

- ^ Laycock, John 1972, p. 28.

- ^ Powers, Ned 1973, p. 12.

- ^ Cosway, John 1972, p. 22.

- ^ Guardian staff 1973, p. 7.

- ^ Evening Standard staff 1973, p. 27.

- ^ Melly, George 1973, p. 35.

- ^ Sun-Herald 1973, p. 90.

- ^ Bennett, Colin 1973, p. 2.

- ^ Nelson, Brian 1975, p. 16.

- ^ Leigh, Spencer 2017, p. 489.

- ^ MGM staff 1982.

- ^ a b Patton, Brad 2010, p. L12.

- ^ Presley, Elvis 2003.

- ^ Presley, Elvis 2005.

- ^ Elvis Week staff 2010.

- ^ Sainz, Adrian 2010, p. 4D.

- ^ Box Office Mojo staff 2021.

- ^ Myers, Marc 2010.

- Sources

- AllMusic staff (2011). "Elvis Presley > Charts & Awards > Billboard Albums". AllMusic. Archived from the original on August 22, 2012. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - Anderson, Nancy (November 14, 1972). "Elvis documentary is designed to please throngs of fans". The Montana Standard. Vol. 97, no. 106. Copley News Service. Retrieved May 24, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- AP staff (April 10, 1972). "Elvis Crowd Sets Record". Press and Sun-Bulletin. Vol. 94, no. 307. Binghamton, New York. Associated Press. Retrieved May 13, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- AP staff 2 (November 13, 1972). "Elvis On Tour big success". Calgary Herald. Associated Press. Retrieved May 24, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - AP staff (January 30, 1973). "Godfather Wins Four Golden Globe Awards". The Cincinnati Enquirer. Vol. 132, no. 296. Associated Press. Retrieved May 19, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Baker, Aron (2021). A Companion to Martin Scorses. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-119-68562-3.

- Bennett, Colin (April 30, 1973). "Elvis goes on forever - and it feels like it". The Age. Vol. 119. Melbourne, Australia. Retrieved May 24, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Billboard staff (August 22, 1970). "Talent in Action". Billboard. Vol. 82, no. 44. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved December 17, 2020.

- Billboard staff (2021). "Elvis Country (I'm 10,000 Years Old) – Chart History". Billboard. Retrieved May 19, 2021.

- Box Office Mojo staff (2021). "Elvis On Tour – Box Office Mojo". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved May 27, 2021.

- Canby, Vincent (June 17, 1973). "How the West Was , and How Elvis Is?". The New York Times. Vol. 122, no. 42, 148. Retrieved May 19, 2021.

- Cosway, John (November 15, 1972). "Fans Still Screaming as Elvis Carries On". Richmond Review. Vol. 39, no. 90. Richmond, British Columbia. Retrieved May 25, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Crouch, Kevin; Crouch, Tanja (2012). The Gospel According to Elvis. Bobcat Books. ISBN 978-0-857-12758-7.

- Doll, Susan (2009). Elvis for Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-56208-6.

- Doll, Susan (2016). The Gospel According to Elvis. Bobcat Books. ISBN 978-0-857-12758-7.

- Eder, Mike (2013). Elvis Music FAQ: All That's Left to Know About the King's Recorded Works. Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 978-1-61713-580-4.

- Edgar, Henry (April 10, 1972). "Presley Reigns Supreme". Daily Press. Vol. 77, no. 101. Newport, Virginia. Retrieved May 13, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Edgar, Henry 2 (April 10, 1972). "Screams, Applause Deafening At Elvis Concert". Daily Press. Vol. 77, no. 101. Newport, Virginia. Retrieved May 13, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Elvis Week staff (March 31, 2010). "Elvis on Tour Being Released on Blu-ray and DVD; Elvis Week Screening Announced". www.elvis.com. Archived from the original on August 14, 2010. Retrieved June 24, 2010.

- Elwood, Phillip (November 2, 1972). "Fascinating Film of 'Elvis On Tour'". The San Francisco Examiner. Vol. 108, no. 124. Retrieved May 24, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Evening Standard staff (February 8, 1973). "Elvis on Tour". Evening Standard. No. 46, 214. London, England. Retrieved May 24, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Glover, William (January 5, 1973). "Elvis Film in Japan Hits $131,311 Mark". Los Angeles Times. Vol. 92. Associated Press. Retrieved May 5, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Graham, Bill (April 19, 1972). "Elvis is the Same – And at His Best". San Antonio Express. Vol. 106, no. 151. Retrieved May 17, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Guardian staff (March 12, 1973). "This Week". The Guardian. London, England. Retrieved May 24, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Guralnick, Peter (1999). Careless Love: The Unmaking of Elvis Presley. Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-33222-4.

- Harris, Winifred (November 1973). "Let The Good Times Roll". American Cinematographer. 54 (11).

- Hopkins, Jerry (2014). Elvis: The Biography. Plexus Publishing. ISBN 978-0-859-65899-7.

- Jeansonn, Glenn; Luhrssen, David; Sokolovic, Dan (2011). Elvis Presley, Reluctant Rebel: His Life and Our Times: His Life and Our Times. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-35905-7.

- Laycock, John (February 2, 1972). "Fans pay to see an advertisement". Windsor Star. Windsor, Canada. Retrieved May 25, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Leigh, Spencer (2017). Elvis Presley: Caught In A Trap. McNidder & Grace. ISBN 978-0-857-16166-6.

- Lenken, Dane (November 18, 1972). "The Real King of Rock 'n' Roll". Montreal Gazette. Vol. 195. Montreal, Canada. Retrieved May 25, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Melly, George (February 11, 1973). "In Praise of Warhol". No. 9472. The Observer. Retrieved May 27, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- MGM staff (1982). Elvis On Tour (VHS). MGM/UA Home Video. MD100153.

- Myers, Marc (August 18, 2010). "The Elvis Enigma". The Wall Street Journal. Associated Press. Retrieved May 26, 2021.

- Nelson, Brian (December 30, 1975). "Elvis special on tv". The Dispatch. Vol. 98, no. 129. Moline, Illinois. Retrieved May 25, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Patton, Brad (August 10, 2010). "Celebrate 75 Years With Elvis". The Times Leader. No. 2010–218. Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. Retrieved May 26, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Pollack, Joe (November 3, 1972). "'Elvis On Tour'". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Vol. 94, no. 304. Retrieved May 24, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Powers, Ned (January 23, 1973). "Visual Treat of Elvis action". The StarPhoenix. Vol. 71, no. 82. Saskatoon, Canada. Retrieved May 25, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Presley, Elvis (2003). Elvis: Close Up (CD). RCA/BMG Heritage. 82876-50537-2.

- Presley, Elvis (2005). Elvis: Close Up (CD). Follow That Dream Records/RCA/BMG. 8287666397-2.

- Raines, Howell (November 10, 1972). "Film Captures Very Little Of Elvis Presley's Appeal". The Atlanta Constitution. Vol. 103, no. 125. Retrieved May 24, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Reed, Billy (November 2, 1972). "'Elvis': Old, new looks at The King". The Courier-Journal. Vol. 235, no. 125. Louisville, Kentucky. Retrieved May 24, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Sainz, Adrian (July 2, 2010). "Revamped Version of 'Elvis on Tour' Coming to Town". Vol. 114, no. 183. Paducah Sun. Associated Press. Retrieved May 26, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Santosuosso, Ernie (November 17, 1972). "'Elvis On Tour' missed the boat". The Boston Globe. Vol. 202, no. 140. Retrieved May 19, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Slaughter, Todd; Nixon, Anne (2014). The Elvis Archives. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-1-783-23249-9.

- Sun-Herald (January 21, 1973). "'Elvis on Tour'". The Sydney Morning Herald. No. 3, 632. Sydney, Australia. Retrieved May 24, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Thomas, Kevin (January 17, 1973). "Elvis Tours His Own Turf". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 19, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Turner Entertainment staff (2010). Elvis On Tour (DVD, Blu-ray). Turner Entertainment Co. 2000041415.

- Victor, Adam (2008). The Elvis Encyclopedia. Overlook Duckworth. ISBN 978-0-715-63816-3.

- Williamson, Joel (2014). Elvis Presley: A Southern Life. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-86318-1.

- Wolff, Kurt (2000). Country Music: The Rough Guide. Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-85828-534-4.