History of Ahmedabad

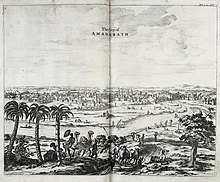

Ahmedabad is the largest city in the state of Gujarat. It is located in western India on the banks of the River Sabarmati. The city served as political as well as economical capital of the region since its establishment. The earliest settlement can be recorded around the 12th century under Chaulukya dynasty rule. The present city was founded on 26 February 1411 and announced as the capital on 4 March 1411 by Ahmed Shah I of Gujarat Sultanate as a new capital. Under the rule of sultanate (1411–1511) the city prospered followed by decline (1511–1572) when the capital was transferred to Champaner. For next 135 years (1572–1707), the city renewed greatness under the early rulers of Mughal Empire. The city suffered due to political instability (1707–1817) under late Mughal rulers followed by joint rule between Maratha and Mughal. The city further suffered following joint Maratha rule. The city again progressed when politically stabilized when British East India Company established the rule in the city (1818–1857). The city further renewed growth when it gain political freedom by establishment of municipality and opening of railway under British crown rule (1857–1947). Following arrival of Mahatma Gandhi in 1915, the city became centre stage of Indian independence movement. Many activists like Sardar Patel served the municipality of the city before taking part in the movement. After independence, the city was a part of Bombay state. When Gujarat was carved out in 1960, it again became the capital of the state until establishment of Gandhinagar in 1965. Ahmedabad is also the cultural and economical centre of Gujarat and the seventh largest city of India.

Early history

[edit]

Chaulukya dynasty

[edit]Al-Bīrūnī mentions Asāval as a trading town on the route from Anhilvada Patan to Cambay.[1][2] In the eleventh century, Karṇa of Caulukya dynasty ruling from Anhilwad Patan (1072–1094) defeated and killed Āśā, the Bhil chieftain of Āśāpallī, near modern Ahmedabad. He then established a temple to the goddess Kocharabā and a temple to the goddess Jayantī at Āśāpallī. He also founded the nearby city of Karṇavatī where he reigned, erected a temple to Karṇeśvara, and excavated a tank called Karṇasāgara. None of these temples have survived to the present-day.[3][4][5][6]

In 1053, the Kaach Masjid mosque was erected in the Tajpur quarter of modern Ahmedabad, only about twenty years after Mahmud of Ghazni's invasion of Gujarat.[7][8]

Delhi Sultanate rule

[edit]According to Jinaprabhā Sūri, there was a battle near Āśāpalli in 1299 between Karṇa of the Vaghela dynasty and Ullu Khāna (Ulugh Khān), general of the Delhi Sultanate ruler 'Alā ud-Dīn, which resulted in Karṇa's defeat and the end of his reign.[9]

Gujarat Sultanate rule (1411–1572)

[edit]

Zafar Khan Muzaffar (later Muzaffar Shah I) of Muzaffarid dynasty was appointed as governor of Gujarat by Nasir-ud-Din Muhammad bin Tughluq IV in 1391.[10] Zafar Khan's father Sadharan, were Tāṅks converted to Islam, adopted the name Wajih-ul-Mulk, and had given his sister in marriage to Firuz Shah Tughlaq. Zafar Khan defeated Farhat-ul-Mulk near Anhilwad Patan and made the city his capital. When the Sultanate was weakened by the sacking of Delhi by Timur in 1398, and Zafar Khan took the opportunity to establish himself as sultan of an independent Gujarat. He declared himself independent in 1407 and founded the Gujarat Sultanate.[2]

The next sultan, his grandson Ahmad Shah I defeated a Bhil or Koli chief of Ashaval, and founded the new city.

Foundation

[edit]- Date

Ahmad Shah I laid the foundation of the city on 26 February 1411[11] (at 1.20 pm, Thursday, the second day of Dhu al-Qi'dah, Hijri year 813[12]) at Manek Burj. He chose it as the new capital on 4 March 1411.[13]

- Legend

Ahmed Shah I, while camping on the banks of the Sabarmati river, saw a hare chasing a dog. The sultan was intrigued by this and asked his spiritual adviser for explanation. The sage pointed out unique characteristics in the land which nurtured such rare qualities which turned a timid hare to chase a ferocious dog. Impressed by this, the sultan, who had been looking for a place to build his new capital, decided to found the capital here.[14]

- Origin of name

Ahmad Shah I, in honour of four Ahmads, himself, his religious teacher Shaikh Ahmad Khattu, and two others, Kazi Ahmad and Malik Ahmad, named it Ahmedabad.[14]

The story is that the king, by the aid of the saint Shaikh Ahmad Khattu, called up the prophet Elijah or Khidr, and from him got leave to build a city if he could find four Ahmads who had never missed the afternoon prayer. A search over Gujarat yielded two, the saint was the third, and the king the fourth. The four Ahmads are said to have been helped by twelve Babas; these were Baba Khoju, Baba Laru, and Baba Karamal, buried at Dholka; Baba Ali Sher and Baba Mahmud buried at Sarkhej; a second Baba Ali Sher who used to sit stark naked; Baba Tavakkul buried in the Nasirabad suburb, Baba Lului buried in Manjhuri, Baba Ahmad Nagori buried near the Nalband mosque, Baba Ladha buried near the Halim ni Khidki, Baba Dhokal buried between the Shahpur and Delhi gates, Baba Sayyid buried in Viramgam. There is a thirteenth Baba Kamil Kirmini about whom authorities are not agreed.[2]

1411–1511

[edit]

Ahmed Shah I laid the foundation of Bhadra Fort starting from Manek Burj, the first bastion of the city in 1411 which was completed in 1413. He also established the first square of the city, Manek Chowk, both associated with the legend of Hindu saint Maneknath. Square in form, enclosing an area of about forty-three acres, and containing 162 houses, the Bhadra fort had eight gates, three large, two in the east and one in the south-west corner; three middle-sized, two in the north and one in the south; and two small, in the west. The construction of Jama Masjid, Ahmedabad completed in 1423. As the city expanded, the city wall was expanded. Ahmed Shah I died in 1443 and was succeeded by his eldest son Muizz-ud-Din Muhammad Shah (Muhammad Shah I) who expanded the kingdom to Idar and Dungarpur. He died in 1451 and was succeeded by his son Qutbuddin Ahmad Shah II who ruled for short span of seven years. After the death of Qutbuddin Ahmad Shah II in 1458, the nobles raised his uncle Daud Khan to the throne. But within a short period of seven or twenty-seven days, the nobles deposed him and set on the throne Fath Khan, son of Muhammad Shah II. Fath Khan, on his accession, adopted the title Abu-al Fath Mahmud Shah but he was popularly known as Mahmud Begada. He received the sobriquet Begada, which literally means conqueror of two forts, probably after conquering Girnar and Champaner forts.[15] So the second fortification was carried out by Mahmud Begada in 1486, the grandson of Ahmed Shah, with an outer wall 10 km (6.2 mi) in circumference and consisting of 12 gates, 189 bastions and over 6,000 battlements as described in Mirat-i-Ahmadi.[16] He planted its streets with trees, adorned the city and suburbs with splendid buildings, and with much care fostered its traders and craftsmen. Though Champaner became capital of the sultanate in 1484, Ahmedabad was still greater, very rich and well supplied with many orchards and gardens, walled, and embellished with good streets, squares, and houses. So closely did he look after its welfare that if he heard of an empty house or shop he ordered it to be filled. In 1509, Ahmedabad trade started to affect by entry of Portuguese. Mahmud died on 23 November 1511.[17]

In the early years of the sultanate, the city reached from Bhadra Fort until Jama Mosque. Between the two buildings settled many merchants, especially arms dealers and luxury goods manufacturers. Eventually various amirs (nobles) set up their own suburban settlements around the city called Puras, of which eventually numbered over a hundred throughout the city's history.[18]

1511–1572

[edit]Mahmud was succeeded by Muzaffar Shah II who ruled until 1526. He was succeeded by Bahadur Shah. During his reign, Gujarat was under pressure from the expanding Mughal Empire under emperors Babur (died 1530) and Humayun (1530–1540), and from the Portuguese, who were establishing fortified settlements on the Gujarat coast to expand their power in India from their base in Goa. He preferred Champaner to Ahmedabad and expanded his reign to central India and to South Gujarat. Bahadur Shah repelled Siege of Diu by Portuguese in 1531 with help of Ottoman Empire and signed Treaty of Bassein. For short period of 1535, Mughal emperor Humayun conquered Gujarat and appointed his brother Aaskari, the governor of Ahmedabad. Bahadur Shah allied with Portuguese and regained power in 1535 but was killed by Portuguese in February 1537. In the disorders that followed his death, the power of the Gujarat Sultans waned, their revenues fell, and the capital, its trade crippled by Portuguese competition, was impoverished and harassed by the constant quarrels of unruly nobles. The capital was shifted back to Ahmedabad in 1537. Following Siege of Diu in 1538, the Portuguese secured the greater part of the profits that formerly enriched the merchants of Ahmedabad. In 1554 the partition of Gujarat among the nobles, leaving to the nominal king Ahmad Shah II (1554–1561), only the city and neighbourhood of Ahmedabad further affected the city. It was captured by Chingiz Khan in 1571 and later by Alaf Khan. In 1571, the city had twelve wards within the walls and others outside. Its chief industries were the manufacture of silk, gold and silver thread, and lac. It yielded a yearly revenue of £155,000 (Rs. 15,50,000) as of 1860.[17]

Social institutions to safeguard various economic interests included the mahajans, guilds of merchants, and panches, guilds for artisans. The leader of the community, who came from the Jain business elites, was known as the nagarsheth, who would resolve disputes between mahajans and individuals and who interceded with royal officials. Under the nagarsheth, the city remained free from interference from the state or other powers.[19]

Mughal rule (1572–1707)

[edit]

Mughal emperor Akbar entered Gujarat and won Anhilwad Patan in 1572. In November 1572, after receiving the submission of its nobles, he made Gujarat a province of his empire, and appointed a governor. When Akbar was gone, the rebel Mirzas connected to Timurid dynasty, backed by some of the Gujarat nobles, came against Ahmedabad in 1573. Two years later in 1575, at a second siege Muzaffar Husain Mirza all but took the city. In 1583 Muzaffar Shah III, the last ruler of Gujarat sultanate, recaptured Ahmedabad and spoiled it of gold, jewels, and fine cloth. Akbar sent Mirza Khan, one of his chief nobles, leading the Mughal army against Ahmedabad. The armies clashed on 22 January 1584 at Sarkhej, after a hard-fought battle, routed Muzzafar's army and forced him to flee to Kathiawar. Raised to be Khan Khanan or head of the nobles, Mirza Khan turned the Sarkhej battlefield into a garden, Fateh Bagh (later Fateh vadi), the garden of victory, for long one of the chief sights of Ahmedabad. Khan Khanan governed the city from 1583 to 1590.[20] In the early years of the seventeenth century Ahmedabad increased in size. Its governor Shaikh Farid Bukhari, or Syed Murtaza, who ruled from 1606 to 1609 founded a new ward Bukhari Mohalla and built Wajihuddin's Tomb. In 1613, a company of thirty-two Englishmen under Mr. Aldworth, the first representatives of British East India Company, came to Ahmedabad. On 15 December 1617, Sir Thomas Roe came to Ahmedabad. About three weeks later on 6 January 1618, Mughal emperor Jahangir gave an audience to him. The Dutch traders also visited him. Jahangir stayed in the city for nine months but was unimpressed by its environment calling it Gardabad, the city of dust. His wife Nur Jahan governed the city during this period.[21]

In 1616 Prince Khurram, afterwards, the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan, was made governor. During his government from 1616 to 1622, he built Moti Shahi Mahal in 1621 and royal baths in the Bhadra fort. Jain merchant Shantidas Jhaveri started building Chintamani Parshwanath temple in Saraspur in 1622.[22] Shortly after (1626), the English traveller Sir Thomas Herbert describes Ahmedabad as "the megapolis of Gujarat, circled by a strong wall with many large and comely streets, shops full of aromatic gums, perfumes and spices, silks, cottons, calicoes and choice Indian and China rarities, owned and sold by the abstemious Banians who here surpass for number the other inhabitants." In 1629 and 1630 Ahmedabad passed through two years of famine known as Satyashiyo Dukal so severe that its streets were blocked by the dying, and those who could move, wandered to other countries. For the poor and destitute soup kitchens, langar-khanas, were established. The famine over, the city soon regained its prosperity. In 1636, Azam Khan started construction of Azam Khan Sarai in Bhadra.[23]

During the next thirty years (1640–1670), the fortunes of Ahmedabad were at their best. The most distinguished governors were Azam Khan (1635–1642), Aurangzeb (1644–1646), and Murad Bakhsh (1654–1657).[failed verification] In 1638, Johan Albrecht de Mandelslo visited the city. During this time the only disorder was in 1644 a riot between Hindus and Muslims in which under Aurangzeb's orders the temple of Chintamani Parswanath near Saraspur was mutilated. Aurangzeb ascended the throne at Delhi 1658. In 1664, the revenue concessions were offered to Europeans and Tavernier came to the city. English Ambassador Sir Thomas Roe visited the city in 1672 again. The jizya tax was imposed on non-Muslims in 1681 and the riots broke out due to famine in the city. The city was flooded up to Teen Darwaza in 1683. Though for several years (1683–1689) affected by attacks of pestilence, Ahmedabad seems to have lost little in wealth. In 1695 it was the headquarters of manufactures, 'the greatest city in India, nothing inferior to Venice for rich silks and gold stuffs curiously wrought with birds and flowers.' With the close of Aurangzeb's (1707) reign began a period of disorder. [24]

During Mughal rule, with the rise of Surat as a rival commercial center, Ahmedabad lost some of its lustre, but it remained the chief city of Gujarat.[19]

Economy

[edit]At the close of the sixteenth century the city was large, well formed, and remarkably healthy; most of its houses were built of brick and mortar with tiled roofs; the streets were broad, the chief of them with room enough for ten ox-carriages to drive abreast; and among its public buildings were large number of stone mosques, each with two large minarets and many wonderful inscriptions. Rich in the produce of every part of the globe, its painters, carvers, in layers, and workers in silver gold and iron, were famous, its mint was one of four allowed to coin gold, and from its Imperial workshops came masterpieces in cotton, silk, velvet and brocade with astonishing figures and patterns, knots and fashions.[24]

Mandelslo, in 1638, describes,

its craftsmen as famous for their work in steel, gold, ivory, enamel, mother of pearl, paper, lac, bone, silk, and cotton, and its merchants as dealing in sugar-candy, cumin, honey, lac, opium, cotton, borax, dry and preserved ginger and other sweets, myrobalans, saltpetre and sal ammoniac, diamonds from Bijapur, ambergris, and musk.

Mughal–Maratha rule (1707–1753)

[edit]With the close of Aurangzeb's (1707) reign began a period of disorder. The Marathas, who had incursions in south Gujarat for about half a century sent an expedition against Ahmedabad upon hearing death of Mughal emperor. Under the command of Balaji Vishwanath, the Marathas won over Mughal army in the Panch Mahals, plundered as far as Vatva within five miles of the city, and were only bought off by the payment of £21,000 (Rs. 2,10,000). In the city the next years were marked by riots and disturbance. In 1709 an order came from the new Mughal emperor Bahadur Shah I (1707–1712), that in the public prayers, among the attributes of the Khalif Ali, the Shia epithet wasi or heir should be introduced. This order caused great discontent among the Ahmedabad Sunnis. They warned the reader not to use the word wasi again, and, as he persisted in obeying orders, on the next occasion they dragged him from the pulpit and stabbed him to death. Three or four years later (1713–1714) another disturbance broke out, this time between the Hindus and Muslims. A Hindu insisting on burning the Holi near some Muslim houses, the Muslims retaliated by killing a cow. On this the Hindus seized a lad the son of a butcher and killed him. Then the Muslims especially the Afghans rose, sacked, and burned shops. They attacked a rich jeweller, Kapurchand, who defended his ward, pol, with matchlock men and killed several of the rioters. For three or four days work was at a standstill. Next year (1715) in the city the riots were renewed, shops were plundered and much mischief done, and outside (1716), the Kolis and Kathis grew so bold and presumptuous as to put a stop to trade.[25]

During the next ten years (1720–1730), the rivalries of the Imperial nobles were the cause of much misery at Ahmedabad. In 1720 Anopsingh Bhandari the deputy viceroy, committed many oppressive acts murdering Kapurchand Bhansali, one of the leading merchants. So unpopular was he that when news reached the city that Shujat Khan had been chosen to succeed him, the people of the town attacked the Bhadra and killed Anopsingh.[25] In 1723 Mubariz-ul-Mulk, Viceroy, chose Shujat Khan his deputy, and Hamid Khan, then holding Ahmedabad for the Nizam the former Viceroy, retired; Shujat Khan took his place, and went to collect tribute, then Hamid returned, defeated and killed Shujat and held all the land about Ahmedabad. Rustam Khan, Shujat's brother, came against Hamid. Hamid won over the Marathas to his side, defeated and killed Rustam, and seized and pillaged Ahmedabad. Then the Viceroy Mubariz-ul-Mulk came and took Ahmedabad (1725). For his services in stopping the pillage of the city Khushalchand, an ancestor of the present Lalbhai family of Ahmedabad, Nagarsheth or chief of the merchants, was raised to that honour.[25]

Then there followed a struggle between Hamid Khan, the Nizam's deputy helped by the Marathas, and Sarbuland Khan the Viceroy and his deputy. During this contest Ahmedabad was pillaged by the Marathas, the city more than once taken and retaken, and even when the Viceroy's power was established in name, he was practically besieged in the city by the crowds of Maratha horse who ravaged the country up to the gates. The revenues cut off, to pay their troops the Mughal officers granting orders on bankers, seized them, put them in prison, and tortured them till they paid. Reduced to wretchedness many merchants, traders, and artisans left the city and wandered into foreign parts. Though successful against the Marathas the Viceroy had to agree to give them a share of the revenue, and badly off for money had, in 1726, and again in 1730, so greatly to increase taxation that the city rose in revolt. In the same year (1730) Mubariz-ul-Mulk the Viceroy, superseded by the king Abhai Singh of Jodhpur, refused to give up the city and outside of the walls fought a most closely contested battle. Under the management of Abhai Singh, Ahmedabad remained unmolested, till in 1733 a Maratha army coming against the city had to be bought off by the payment of a large sum of money.[26]

In 1737 a fresh dispute arose among the Mughal officers. Momin Khan the Viceroy had his appointment cancelled in favour of Abhesingh's deputy Ratansingh Bhandari. Refusing to obey the second order, Momin Khan by the promise of half of the revenues of Gujarat and half of Ahmedabad, won Damaji Rao Gaekwad to his side, and bombarding the city, after a siege of some months, captured it in 1738. According to agreement the city was divided between Khan and the Gaekwad's agent Rangoji. The Maratha share was the south of the city including the command of the Khan Jahan, Jamalpur, Band or closed, also called Mahudha, Astodiya, and Raipur gates. This joint rule lasted for fifteen years (1738–1753).[27]

The fifteen years of Mughal–Maratha joint rule was a time of almost unceasing disturbance. Within the city Momin Khan, till his death in 1743, held without dispute the chief place among the Muslims. For a short time after Momin Khan's death, power (1743) passed into the hands of Fida-ud-din Khan. It was then usurped by Jawan Mard Khan, and he, in spite of the attempts of Muftakhir Khan, afterwards Momin Khan II. (1743), and Fakhrud-daulah (1744–48) the nominal Viceroys, held it during the ten remaining years. Meanwhile, the cunning and greed of the Marathas caused unceasing trouble and disorder. Driven out in 1738, before a year was over they forced themselves back. Again in 1742 the Muslims rose against them, kept them out of power for about two years, and for a time held their leader Rangoji a prisoner. Escaping from confinement, Rangoji next year (1744) returned and forced Jawan to give him his share of power. Acknowledging their claims for some years, Jawan, in 1750, when Damaji Gaekwad was in the Deccan, again drove the Marathas out of the city. For two years Jawan remained in sole power, till in 1752 the Peshwa, owning now the one-half of the Gaekwad's revenues, sent Pandurang Pandit to collect his dues. Shutting the gates Jawan succeeded in keeping the Marathas at bay.[27] But knowing his weakness he admitted their claim to share the revenue and allowed their deputies to stay in his town. Next year (1753) when Jawan was in Palanpur collecting revenue, the Peshwa and Gaekwad with from 30,000 to 40,000 horse, suddenly appearing in Gujarat, pressed north to Ahmedabad. The people, leaving the suburbs, fled within the walls. And the Marathas unopposed invested the city with their 30,000 horse, the Gaekwad blockading the north, Gopal Hari the east, and the Peshwa's deputy Raghunath Rao watching the south and west. Message after message sent to Jawan as he moved about the country, failed to reach him. One at last found him and starting with 200 picked horsemen he passed during the night through the Maratha lines and safely entered the city. Cheering the garrison they defended the city with vigour, foiling an attempt to surprise and driving back an open attack. Their deputies turned out of the city and Jawan's garrison gradually strengthened from outside, the Maratha chances of success seemed small. But Jawan was badly off for money, and, in spite of levies on the townspeople, he could not find enough to pay his troops. Terms were agreed on, and, giving Jawan a sum of £10,000 (Rs. 1,00,000), the Marathas in April 1753 entered Ahmedabad.[28]

The siege had done the city lasting harm. The suburbs, deserted at the approach of the Marathas, were never re-peopled. The excessive greed of the Marathas as sole rulers of Ahmedabad caused great discontent. Knowing this, and learning that heavy rain had made great breaches in the city walls, Momin Khan II advanced from Cambay. Some of his men, finding a passage through one of the breaches, opened the gates, and his troops rushing in drove out the Marathas December 1755. Calling on Momin Khan to surrender, the Marathas at once invested the town. For more than a year the siege lasted, Momin Khan and his minister Shambhuram a Nagar Brahman, driving back all assaults, and at times dashing out in the most brilliant and destructive sallies. But the besieged were badly off for money, the pay of the troops was behind, and the people already impoverished were leaving the city in numbers. Tho copper pots of the runaways kept the garrison in pay for a time. But at last this too was at an end, and after holding out for a year and a quarter Momin Khan, receiving £10,000 (Rs. 1,00,000), gave up the city (April 1757).[28]

Maratha rule (1758–1817)

[edit]

The Peshwa and Gaekwad divided the revenues, the Peshwa, except that the Gaekwad held one gate and that his deputy remained in the city to see that his share of the revenue was fairly set apart, undertaking the whole management of the city. For nearly twenty-three years the city remained in Maratha hands. During the First Anglo–Maratha War (1775–1782), General Thomas Wyndham Goddard, acting in alliance with Fateh Singh Gaekwad against the Pune, with 6,000 troops stormed Bhadra Fort on 12 February 1779. His army made breach at Khan Jahan gate and captured Ahmedabad on 15 February 1779. There was a garrison of 6,000 Arab and Sindhi infantry and 2,000 cavalry. Losses in the fight totalled 108, including two Britons. After the war, the city was later handed to Fateh Singh Gaekwad who held it for two years. The city was severely damaged and depopulated and the economy was destroyed.[29][30] Under the terms of the under the Treaty of Salbai (24 February 1783) Ahmedabad was restored to the Peshwa, the Gaekwad's interest being as before, limited to one-half of the revenue and the command of one of the gates. For some years tho city improved, its manufactures in 1789 being incomparably better than those of Surat. Then the 1790 famine caused fresh distress, and a few years later only a quarter of the space within the walls was inhabited. At this time (1798–1800) Aba Salukar, tho Peshwa's Governor, indebted and oppressive, ill-used the people, and embezzled the Gaekwad's revenues. Advancing against Salukar, Govind Rao Gaekwad defeated him near Shah e Alam and, pursuing him into the citadel, made him prisoner. On this the Peshwa, who from private dislike to Aba was secretly pleased, granted the Gaekwad, for a yearly payment of £50,000 (Rs. 5,00,000), a five-year lease of his share of the Gujarat revenues. This arrangement, renewed for ten years in 1804, continued in force till 1814. Though the city was considerably recovered, the famine in 1812 devastated its people. After the Second Anglo-Maratha War, the British East India Company had gained considerable political power and territories. When Peshwa appointed Trimbak Dengle as governor on 23 October 1814, the relationship between Gaekwad and Peshwa deteriorated. Gaekwad sent an envoy to the Peshwa in Pune to negotiate a dispute regarding revenue collection. The envoy, Gangadhar Shastri, was under British protection. He was murdered, and the Peshwa's minister Trimbak Dengle was suspected of the crime. The British seized the opportunity to force Baji Rao II sign the Treaty of Poona (13 June 1817). Under the terms of the treaty, the Peshwa agreed, for a yearly payment of £45,000 (Rs. 4,50,000), to let in perpetuity to the Gaekwar the farm of Ahmedabad. Under the same treaty the Peshwa agreed, that this revenue from the Ahmedabad farm, should be paid by the Gaekwar to the British as part of the British claims on the Peshwa's revenues. A few months later (6 November 1817), it was arranged with the Gaekwad that he should, in payment of a subsidiary force, cede to the British the rights he had obtained under the Peshwa's farm, and, in exchange for territory near Baroda, give up his own share in the city of Ahmedabad. The only exception to this transfer was that the Gaekwad was allowed to keep his fort, Gaekwad Haveli, in the south-west corner of the city. In 1753, the armies of the Maratha generals Raghunath Rao and Damaji Gaekwad captured the city and ended Mughal rule in Ahmedabad. A famine in 1630 and the constant power struggle between the Peshwa and the Gaekwad virtually destroyed the city. Many suburbs of the city were deserted and many mansions lay in ruins.[31][32]

British company rule (1817–1857)

[edit]Dunlop, British Collector of Kaira took over administration of the city in 1818. In June 1819, Rann of Kutch earthquake hit the city damaging several monuments and houses in the city. The political stability, establishment of order and the lowering of the taxes, gave a great impetus to trade and the city was for a time busy and prosperous. The population rose from 80,000 in 1817 to about 88,000 in 1824. During the eight following years a special cess was levied on ghee and other products and at a cost of £25,000 (Rs. 2,50,000) the city walls were repaired. About the same time a cantonment was established on a site to the north of the city, chosen in 1830 by Sir John Malcolm. These (1825–1832), though some of them years of agricultural depression and dull trade, brought a further increase of population to 90,000. In the next ten years the state of the city improved. The population rose (1816) to about 95,000. The Hutheesing Jain Temple, completed in 1848, and other buildings of that time (1844–1846) show that some of the city merchants were possessed of very great wealth. The public funds available after the walls were finished were made use of for municipal purposes. Streets were widened and thoroughfares watered. During the following years the improvement continued. Ahmedabad's gold, silk, and carved-wood work again (1855) became famous, and its merchants and brokers enjoyed a name for liberality, wealth and enlightenment.[33]

During the rebellion of 1857, the government quickly contained the mutineers of the Gujarat Irregular Horse and of the 2nd Grenadier Regiment. On the arrival of the 86th Regiment in January 1858, the city was disarmed, when 25,000 arms chiefly matchlocks and swords were surrendered.[34]

British crown rule (1857–1947)

[edit]

From 1857 to 1865, it was a time of great prosperity. The municipal government was established in 1858. The American Civil War (1863–1865) helped the economy of the city. The railway connecting Ahmedabad with Bombay was opened in 1864. Ahmedabad grew rapidly, becoming an important center of trade and textile manufacturing. The city was greatly damaged by floods in 1868 and in 1875.[35]

In 1877, the city suffered from fire. On 27 January 1877, there was an explosion of gunpowder in a Bohora's shop. This shop, in which were more than 500 pounds of gunpowder, was about ten at night found to be on fire. The gunpowder exploded burning five shops and killing eighty-eight people. Two months later, on the night of 24 March 1877, a fire broke out in the chief enclosure, pol, of the Sarangpur area. The street was very narrow and lined with four-story high houses. It was only with the greatest difficulty that the fire engines could be brought to play on the fire. Military help was called in and by ten next morning the fire was got under, but not until ninety-four houses had been burned and property worth £60,000 (Rs. 6,00,000) destroyed.[35]

In 1878, the lower classes suffered from high prices of food-grains while the upper classes from the dullness of trade and losses in Bombay mills.[35]

The old mercantile and industrial elite, with their relative sophistication in matters of industry, trade, and financing, were well poised to expand under British rule, using their own financing for new technology, represented by British machinery. Instead of just a few merchants introducing new industrial machinery, as elsewhere in India, in Ahmedabad the mercantile class as a whole supported the new techniques, even though hand spinners and handloom weavers, as well as female spinners in the outlying communities had their traditional operations upset as a result. They and others were recruited into the new manufacturing plants. The merchant class tended to support the British, thinking the rule provided more security than under the Marathas, lower taxes (including lower octroi), and more property rights.

Unlike most other areas of India, British rule meant no major upsetting of the community's traditional social system, although the traditional peasant landowning class, the Banias and Patidars, were absorbed into the Jain business community. The British did not have a financing vacuum to fill in the city, so their presence was limited to administrative and military spheres. Unlike other Indian cities, Ahmedabad lacked a comprador class or dominant, Western-educated middle class. Western education was slower to be introduced into the city than in most other Indian cities. There was very little English higher education available in the city and no English-language newspapers there in the 19th century.[19]

Instead of education in English language and culture, technology education was promoted in the late 19th century. Ranchhodlal Chhotalal, the Nagar Brahmin who founded a spinning and weaving company in the city in 1859, ordered the city to withdraw its support for a high school in 1886 and instead finance technical education. Starting in 1889, the city financed scholarships for technical students. With no Western-oriented academic center in the city, there was no opposing political reaction to Western influences, and the city. "The entire discourse of tradition versus modernity, thrown up by exposure to Western literature and culture, was almost non-existent in Ahmedabad," according to literary scholar Svati Joshi.[19]

Schools for girls, primarily for those in the upper classes, were founded in the mid-19th century. Maganbhai Karamchand, a Jain businessman, and Harkor Shethani, a Jain widow. One visitor, Mary Carpenter, wrote in 1856 after visiting the city, "I found how very far behind Ahmedabad these other places [like Calcutta] were in effort to promote female education among the leading Hindus, in emancipation of the ladies from the thraldom imposed by custom; and in self-effort for improvement on their own part."[19]

The struggle for independence from the British soon took roots in the city. In 1915, Mahatma Gandhi came from South Africa and established two ashrams in the city, the Kochrab Ashram near Paldi in 1915 and the Satyagraha Ashram on the banks of Sabarmati in 1917. The latter was later called Harijan Ashram or Sabarmati Ashram. He started the salt satyagraha in 1930. He and many followers marched from his ashram to the coastal village of Dandi, Gujarat, to protest against the British imposing a tax on salt. Before he left the ashram, he vowed not to return to the ashram until India became independent.

Post independence (1947–)

[edit]By 1960, Ahmedabad had become a metropolis with a population of slightly under half a million people, with classical and colonial European-style buildings lining the city's thoroughfares. After independence, Ahmedabad became a provincial town of Bombay state. On 1 May 1960, Ahmedabad became a state capital as a result of the bifurcation of the state of Bombay into two states of Maharashtra and Gujarat following Mahagujarat Movement. During this period, a large number of educational and research institutions were founded in the city, making it a centre of higher education, science and technology.[36] Ahmedabad's economic base became more diverse with the establishment of heavy and chemical industry during the same period. At that time the city was seen as an economic role model around the world. Many countries sought to emulate India's economic planning strategy and one of them, South Korea, copied the city's second "Five-Year Plan" and the World Financial Center in Seoul is designed and modelled after Ahmedabad. Ahmedabad had both a municipal corporation and the Ahmedabad Divisional Council in the 1960s, which developed schools, colleges, roads, municipal gardens, and parks. The Ahmedabad Divisional Council had working committees for education, roads, and residential development and planning.

In the late 1970s, the capital shifted to the newly built, well-planned city of Gandhinagar. This marked the start of a long period of decline in the city, marked by a lack of development. In February 1974, Ahmedabad occupied the centre-stage of national politics with launch of the Navnirman agitation. It started off as an argument over a 20% hike in hostel food bill in the L.D. College of Engineering, but ignited an agitation which later snowballed into the Nav Nirman movement. This movement caused the then chief minister of Gujarat, Chimanbhai Patel, to resign and also gave Indira Gandhi one of the excuses for imposing the Emergency on 25 June 1975.[37][38]

In the 1980s, a reservation policy was introduced in the country, which led to anti-reservation protests in 1981 and 1985. The protests witnessed violent clashes between people belonging to various castes.[39]

On 26 January 2001, a devastating earthquake centred near Bhuj, measuring 6.9 on the richter scale, struck the city. As many as 50 multistoried buildings collapsed killing 752 people.[40] The following year, a three-day period of violence between Hindus and Muslims in the western Indian state of Gujarat, known as the 2002 Gujarat violence, spread to Ahmedabad; refugee camps were set up around the city and economy was affected.[41] Sabarmati Riverfront project started in 2004. The 2008 Ahmedabad bombings, a series of seventeen bomb blasts, killed and injured several people.[42] Militant group Harkat-ul-Jihad claimed responsibility for the attacks.[43] Ahmedabad BRTS was inaugurated in 2009. The construction of Ahmedabad Metro began in 2015 and the operation began in March 2019.

References

[edit]- ^ Sheikh, Samira (2010). Forging a Region: Sultans, Traders, and Pilgrims in Gujarat, 1200-1500. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-908879-9.

- ^ a b c Google Books 2015, p. 250.

- ^ Majumdar, Asoke Kumar (1956). Chaulukyas of Gujarat: A survey of the history and culture of Gujarat from the middle of the tenth to the end of the thirteenth century. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. pp. 60, 65.

- ^ Merutunga Ācārya (1901). The Prabandhacintāmani or Wishing Stone or Wishing Stone of Narratives. Translated by Tawney, C. H. The Asiatic Society. p. 80.

- ^ Mishra, Vibhuti Bhushan (1973). Religious Beliefs and Practices of North India During the Early Mediaeval Period. E. J. Brill. pp. 29–30.

- ^ Dhaky, M.A. (1961). Deva, Krishna (ed.). "The Chronology of the Solanki Temples of Gujarat". Journal of the Madhya Pradesh Itihasa Parishad. 3: 37.

- ^ Chagtai, M.A. (1939). "The Earliest Muslim Inscription in India from Ahmedabad". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 3: 647–648. JSTOR 44252418 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Majumdar 1956, p. 332.

- ^ Majumdar 1956, p. 187-189.

- ^ Google Books 2015, p. 249.

- ^ Pandya, Yatin (14 November 2010). "In Ahmedabad, history is still alive as tradition". dna. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- ^ "History". Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation. Archived from the original on 23 February 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

Jilkad is anglicized name of the month Dhu al-Qi'dah, Hijri year not mentioned but derived from date converter

- ^ Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency: Ahmedabad. 7 January 2015. p. 249. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ a b "Lonely planet". Lonely Planet.

- ^ Bloom, Jonathan; Blair, Sheila (2009). Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art & Architecture. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 37–39. ISBN 978-0-19-530991-1.

- ^ G. Kuppuram (1988). India through the ages: history, art, culture, and religion. Vol. 2. Sundeep Prakashan. p. 739. ISBN 9788185067094.

- ^ a b Google Books 2015, p. 251.

- ^ Mehta, R.N.; Jamindar, Rasesh (1988). "Urban Contact". In Michell, George; Shah, Snehal (eds.). Ahmadabad. Marg Publications. pp. 18–19.

- ^ a b c d e Blackburn, Stuart H., and Vasudha Dalmia, editors, India's Literary History, "Chapter 11: Dalpatram and the Nature of Literary Shifts in Nineteenth-Century Ahmedabad" by Svati Joshi, pp 338–357, published by Orient Blackswan, 2004 ISBN 9788178240565, retrieved Google Books (partial) version, 16 December 2008

- ^ Google Books 2015, p. 252.

- ^ Google Books 2015, p. 253–254.

- ^ M. S. Commissariat, ed. (1996) [1931]. Mandelslo's Travels in Western India (reprint, illustrated ed.). Asian Educational Services. p. 101. ISBN 978-81-206-0714-9.

- ^ Google Books 2015, p. 254–255.

- ^ a b Google Books 2015, p. 255.

- ^ a b c Google Books 2015, p. 256.

- ^ Google Books 2015, pp. 256–257.

- ^ a b Google Books 2015, p. 257.

- ^ a b Google Books 2015, p. 258.

- ^ Duff, James Grant (1826) [Oxford University]. A History of the Mahrattas. Vol. 2. London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green.

- ^ Beveridge, Henry (1862) [New York Public Library]. A comprehensive history of India, civil, military and social. Blackie. pp. 456–466.

ahmedabad.

- ^ "Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation – History of Ahmedabad". Archived from the original on 27 February 2006. Retrieved 10 May 2006.

- ^ Google Books 2015, pp. 259–260.

- ^ Google Books 2015, pp. 260–261.

- ^ Google Books 2015, p. 261.

- ^ a b c Google Books 2015, p. 262.

- ^ Political Science. FK Publications. 1978. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-81-89611-86-6. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ "When LD Engineering structured the revolt". Retrieved 10 May 2006.

- ^ Ghanshyam Shah (20 December 2007). "60 revolutions—Nav nirman movement". India Today. Retrieved 3 July 2008.

- ^ Achyut Yagnik (May 2002). "The pathology of Gujarat". New Delhi: Seminar Publications. Retrieved 10 May 2006.

- ^ Anil Sinha. "Lessons learned from the Gujarat earthquake". WHO Regional Office for south-east Asia. Archived from the original on 19 June 2006. Retrieved 13 May 2006.

- ^ "Gujarat riot death toll revealed". BBC News. 11 May 2005. Retrieved 30 July 2006.

- ^ "17 bomb blasts rock Ahmedabad, 15 dead". CNN IBN. 26 July 2008. Archived from the original on 28 June 2008. Retrieved 26 July 2008.

- ^ "India blasts toll up to 37". CNN. Turner Broadcasting System. 27 July 2008. Archived from the original on 2 August 2008. Retrieved 27 July 2008.

Notes

[edit]- Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency: Ahmedabad. 7 January 2015. pp. 248–262. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help)