Our Big Mac index shows how burger prices differ across borders

Using patty-power parity to think about exchange rates

The big mac index was invented by The Economist in 1986 as a lighthearted guide to whether currencies are at their “correct” level. It is based on the theory of purchasing-power parity (PPP), the notion that in the long run exchange rates should move towards the rate that would equalise the prices of an identical basket of goods and services (in this case, a burger) in any two countries.

Burgernomics was never intended as a precise gauge of currency misalignment, merely a tool to make exchange-rate theory more digestible. Yet the Big Mac index has become a global standard, included in several economic textbooks and the subject of dozens of academic studies. For those who take their fast food more seriously, we also calculate a gourmet version of the index.

The GDP-adjusted index addresses the criticism that you would expect average burger prices to be cheaper in poor countries than in rich ones because labour costs are lower. PPP signals where exchange rates should be heading in the long run, as a country like China gets richer, but it says little about today’s equilibrium rate. The relationship between prices and GDP per person may be a better guide to the current fair value of a currency.

In July 2022 we updated the Big Mac index to use a McDonalds-provided price for the United States. We also changed our methodology for how we calculate the GDP-adjusted index, the full history of which will now be adjusted whenever the IMF’s historical GDP series are updated. The previously published versions of both indices are available in our archive.

Read more about the Big Mac index in “What Donald Trump can learn from the Big Mac index”. You can also download the data or read the methodology behind the Big Mac index here.

Note: The GDP-adjusted index was updated in January 2021 to include more countries.

Correction (January 26th 2023): An earlier version of the index had the wrong Big Mac price for China in January 2024. Sorry.

More from Finance & economics

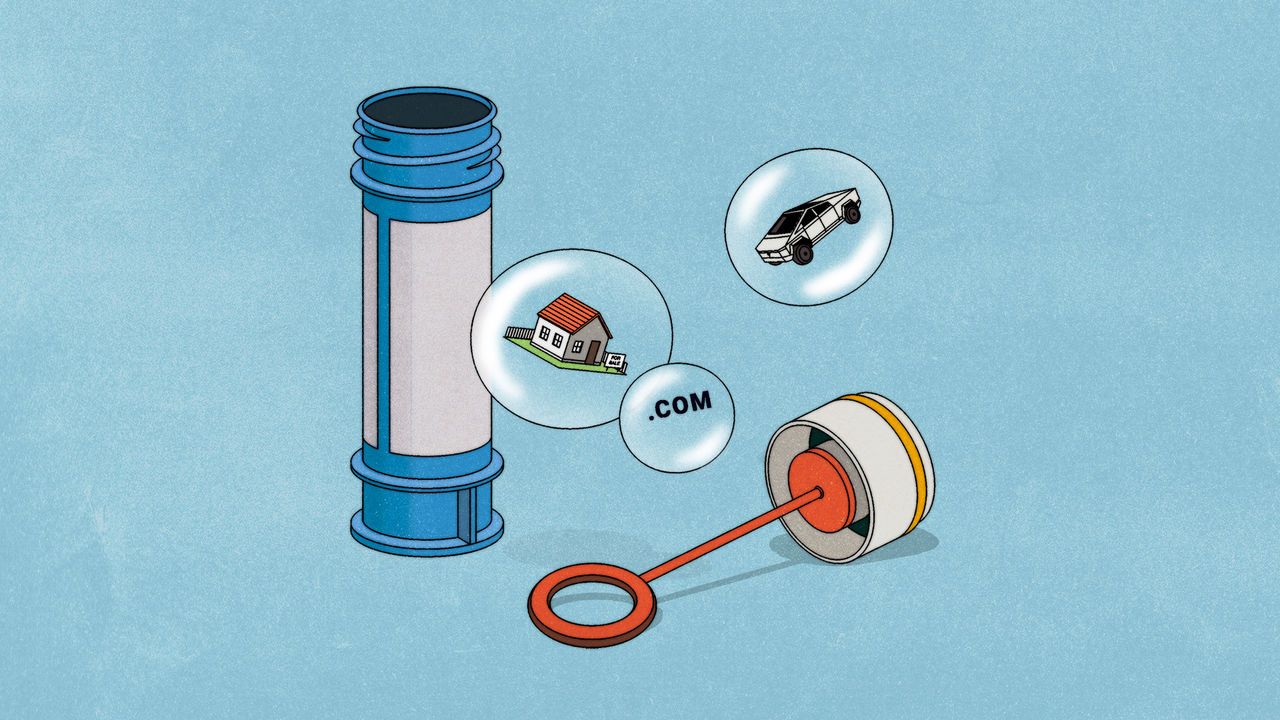

Would an artificial-intelligence bubble be so bad?

A new book by Byrne Hobart and Tobias Huber argues there are advantages to financial mania

Will Elon Musk dominate President Trump’s economic policy?

He will face challenges from both America firsters and conservative mainstreamers

What investors expect from President Trump

Shareholders are over the moon; bondholders are readying the whip hand

China’s firms are taking flight, worrying its rulers

Policymakers at home and abroad are anxious about offshoring

Manmohan Singh was India’s economic freedom fighter

India’s most consequential finance minister, who later became PM, has died aged 92

Why fine wine and fancy art have slumped this year

Investing in luxury goods was a bad move in 2024