LONDON: It’s been at the heart of London’s identity for decades: Bakers and bankers live on the same city streets in patchwork neighborhoods where swank mansions sit in the shadow of grim tower blocks, and residents from all walks of life mingle in shops, schools and subway stations.

Now Britain’s debt-shredding austerity measures will slash housing benefit payments used to subsidize rents for the low-paid, threatening to price tens of thousands of poor families out of their homes and force them toward the fringes of the country’s capital – an exodus that could permanently erode London’s famed ethnic, economic and cultural mix. Outspoken London Mayor Boris Johnson likens the plan to “Kosovo-style social cleansing.”

Some fear London will become more like Paris, where rich elites monopolize the city center and the poor stagnate in decaying housing projects ringing the capital.

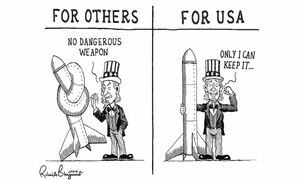

But in tough times, others wonder if Britain can still afford to help ordinary workers find homes in a city center that keeps getting pricier, even as the overall economy shows only sluggish growth.

As part of 81 billion pounds ($128 billion) of spending cuts announced last week to help wipe Britain's crippling debts, limits will be placed on the amount given to the poor to help them pay their rent.

One estimate predicts an exodus of about 200,000 people from central London, with low earning families forced toward down-at-heel outer suburbs and far-flung commuter towns — leaving the capital’s streets reserved for the rich.

Critics worry the famously rowdy working class enclaves of London’s East End – which gave Britain its defiant wartime spirit of the Blitz – will fall silent, and that the city’s multicultural character could be lost.

“One of the best things about London is precisely that it is not like Paris – you have very rich people and people in social housing all living along the same street,” said Sian Berry, a former candidate for London mayor and part of the “No Shock Doctrine” campaign protesting against the government’s cuts.

“Those people all use the same public services, the same shops, the same schools and the same transport – it helps make people more tolerant of each other,” she said.

Under the government’s plans, which will be debated in Parliament and are yet to be finalized, a new limit will be set for the maximum amount families can claim to pay for privately rented homes, and no family will be able to use welfare payments to rent a home with more than 4 bedrooms.

Britons who earn less than 16,000 pounds (US$25,500) per year and have only limited savings are entitled to claim housing benefit – which can be used to rent a house or flat, but not for mortgage payments.

Those who rent from private landlords have their benefits calculated using an average rental price in their local area. Until now, benefits have helped make sure people can afford the cheapest 50 percent of properties up for rent in their district; next October that will be reduced to the cheapest 30 percent. From April, payments will be capped at 250 pounds ($400) per week for a one-bedroom apartment and at 400 pounds ($640) per week for a four-bedroom house.

If rents are higher than the cap, tenants must make up the difference – or leave town.

“It is hard enough to scrounge up enough money every month as it is. If the changes go through, we will definitely have to move,” said Lena Tedesco, a 36-year-old unemployed mother from Camden, in north London.

Tedesco has three children aged under 6, and already uses money from sporadic cleaning jobs to top up her housing benefit and meet the cost of a two-bedroom apartment.

Like many benefit claimants, Tedesco said she’s terrified that under the changes she’ll no longer be able to make ends meet.

“I know it’ll involve moving, probably outside London – it’s absurd,” she said. “We’d have to move away from our family, friends, look for another school. Its very upsetting.”

Campbell Robb, chief executive of housing charity Shelter, said the welfare cuts could “change the face of London forever.”

“We are extremely concerned that this will not only lead to increased levels of homelessness and overcrowding, but will mean children ripped out of their schools, and families forced miles away from their jobs and communities in search of an affordable place to live,” Robb said.

London Councils, an umbrella group that represents the capital's local authorities, estimates 82,000 households – the equivalent of about 200,000 adults and children – could be priced out of their current home.

Sought-after districts like Westminster, Chelsea, Kensington and Camden _ which host a mix of exclusive homes and modest apartment blocks – would become “no-go” areas for the poor, the organization said.

John Reiss, a 47-year-old garbage collector who lives in Camden, said the changes would force him to move and find a new job. “I probably wouldn’t be able to stay in London. It would turn my whole world upside down,” he said.

Prime Minister David Cameron is axing 18 billion pounds (US$29 billion) from the country’s welfare bill to help pare down on Britain’s budget deficit. Already, he has angered middle-class voters with plans to scrap child benefit payments to about 1.5 million families. The outcry over housing welfare shows the difficulties he will face driving through a harsh five-year program of cuts.

But supporters of the new housing plan say Britain can’t ignore the fact house prices and rents are sky-high in inner city London, where once rundown neighborhoods were transformed in the boom years.

Opponents are “trying to deny the basic reality that it will tend to be richer people living in more expensive areas,” said Matthew Sinclair, of the Taxpayers’ Alliance campaign group.

Defending the plan in the House of Commons, Cameron said the majority of the public was “working hard to give benefits to other people to live in homes that they themselves cannot dream of, and I do not think that is fair.” Karen Buck, a Labour party legislator who represents the Westminster North district in Parliament, said that — while some extreme cases involve benefit claimants receiving large sums to live in sought-after streets — most of the 5 million people who get public help paying rent are struggling low-paid workers who end up living in modest quarters in ordinary neighborhoods.

“There are an overwhelming majority of people who are claiming benefit to keep a roof over their heads, simply because they don't earn enough money,” Buck said. Labor unions have long warned that many people in ordinary jobs — nurses, teachers and care workers — can’t afford a home in the city. Figures uncovered by Buck show almost half of London police officers already live outside the capital.

“Cities are dynamic, but if you force social change at the scale and pace that this could mean, then are you heading for trouble,” Buck said. — AP

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.