Update December 2, 2024 (originally published Jan. 13, 2020):

On this cyber Monday, we’re republishing this expose of Amazon’s terrible disposable tech. Since 2020, things haven’t gotten any better—and in some ways, they’ve gotten worse.

Amazon’s own hardware has become increasingly dominant (having sold hundreds of millions of Kindles, Fire TVs, and Alexa-enabled devices), and they still just replace broken things, refurbishing some but trashing a lot. No authorized repair shops. No parts for sale. Just replacement, if your item’s under warranty.

A few more recent Amazon demerits:

- UK TV station ITV News investigated and found that Amazon destroys millions of products a year in the UK alone.

- Amazon cut out small-scale refurbishers (like long-time iFixit user John Bumstead, aka rdklinc) from their marketplace.

- Amazon shut down their Halo fitness and sleep tracking hardware division—and all these devices became e-waste when their software stopped being supported.

- There’s a big Amazon-sized loophole in the Digital Fair Repair Act that passed in Minnesota last year: Manufacturers are exempt from the law if they provide a replacement device at no cost to the consumer (see p. 172 of the omnibus bill).

But there is some hope: In May 2024, the EU Parliament banned the destruction of unsold textiles—and may include electronics in the future. The law enters into force two years after its enactment.

It’s time for us, as consumers and as stewards of our planet, to rethink our buying habits. Remember that the allure of a shiny new device on Prime Day has an environmental price tag. Demand better. Demand that Amazon takes responsibility for the lifecycle of its products, from production to end-of-life.

Amazon offers a flotilla of “smart” devices to replace your microwave, kids’ nightlights, wall plugs, and, coming soon, rings and eyeglasses. But the company’s barely-noticeable effort to recycle or help people repair these things is dumb, and it’s costing our planet a whole lot. It’s time people stop giving Amazon’s cheap products a pass on responsible stewardship. The retail giant has the resources to do so much better.

And that’s before we even talk about Fire tablets.

Amazon doesn’t repair their own products for customers outside their return or warranty periods. The company doesn’t make parts available. Need a new battery for your old but still functional Kindle Paperwhite? That’s too bad, Amazon doesn’t sell them directly (though you can roll the dice on a number of third-party vendors). The same goes for microwaves and nightlights. And even after you’ve given up on fixing something, Amazon’s recycling and trade-in programs for its own products exist, but they’re drastically under-promoted.

The impact of Amazon’s cheap, hard-to-fix gear is ignored or obscured at every level. The company’s environmental report talks about a “circular economy” mostly in the context of refurbished goods customers can buy. Customers, it reads, “may discover” a device recycling program or trade-in programs (we had no idea either existed, and you likely didn’t, either). On a human scale, an iFixit staffer who twice received a keyboard with a missing part was told by different Amazon customer support reps to “just simply thrown into trash” (sic) and “just [give] it to garbage man, they will separate that.”

That this goes overlooked is odd, as Amazon’s impact on everything has gotten attention lately. The dangers and small business pinch of “free” delivery, the mire of fake reviews, the privacy invasions of Ring video doorbells or Alexa/Echo devices, even the impact of Cyber Monday cardboard: we’re all starting to think more critically about Amazon’s all-consuming reach.

Yet at the same time, way too many of us are okay with buying, gifting, or recommending cheap Amazon tech as disposable, good-enough solutions. Tech review sites with otherwise critical eyes regularly recommend underwhelming Fire tablets as kid’s toys or streaming screens, eagerly announce when Echo devices go on sale, and never mention where all those cheap devices end up when they age, break, or become obsolete.

In response to this post, and questions about the company’s recycling and repair programs posed before publication, an Amazon spokesperson noted the company’s pledge to be carbon-neutral by 2040. Refurbishment and trade-in programs have “kept millions of devices from ending up in landfills in 2019 alone,” and many Amazon products are still in use after five years, according to a statement from the spokesperson.

The statement did suggest Amazon is aware that more work is needed.

“While we have been focused on sustainability for many years, such as through our recycling, refurbishment and trade-in programs, we know we have more work to do to allow our customers to make informed choices and to provide transparent information about the environmental impacts of devices through their whole life cycle,” Amazon’s spokesperson stated.

Nobody seems to be asking of Amazon the same kind of device stewardship that we ask of Apple, Google, Microsoft, or even smaller brands. Maybe it’s due to the largely transactional relationship people have with the mega-store. Maybe it’s because people simply tolerate Amazon’s tech gear, rather than truly enjoy it, even when it’s new.

The New, Already Outdated Fire Tablet

Fire Tablets are low-end Android devices optimized for Kindle reading, streaming video, Alexa commands, and simple games. The goal is to feed you Amazon’s services and validate your $120 yearly Prime membership. Inside the current 7- and 8-inch versions ($50 and $80 respectively, though they’re often on sale for less) is a MediaTek MT8163V/B all-in-one chipset. That chip is actually slower than the one in Samsung’s Galaxy S5, released in early 2014 1. Fire tablets can functionally run one Amazon app at a time, but trying to flip between apps or do actual work feels like trying to get a teenager to wake up and rake leaves.

There are loads of cheap, underperforming tablets available, but Amazon’s aggressive pricing, tie-in services, and outsized brand power have a reality distortion effect on buyers and otherwise hyper-critical reviewers. They’re cheap, the thinking goes; even cheaper with ads on them. At such prices, you can toss it in your bag to watch videos while traveling, or let your kids beat it up. Most people wouldn’t clutter their home with a no-name, underpowered Android tablet bought on a whim, but they’ll take one from Amazon.

Wirecutter states the HD 8 is “great for consuming Amazon-provided content, but it’s not as flexible as a full-fledged Android tablet.” But at $95 ($80 with lockscreen ads), it’s “a tolerable trade-off when you need a media-consumption tablet on the cheap.” The Verge gives the newest $150 10-inch Fire a seven out of 10, but notes it “Feels as cheap as it costs” and is “Slow for a 2019 device.” This is not to single out those two sites; they’re reviewing products in a particular reader-service context. Many other tech sites push cheap tablets with far less pondering.

But the net result of this very slick sales funnel is a lot of rare materials pulled from the earth, energy used to make tablets already past their prime, fuel used to ship them, and then, when they can’t be fixed or efficiently disassembled, a huge pile of shredded plastic, circuit boards, and, more than likely, hazardous batteries.

I called a local store in a national repair chain to ask if they repaired Kindle Fire tablets. “I’m gonna be honest with you, the price of repairing that is going to be equal to or more than replacing it,” an employee there told me. “Like $50 or $75?” I asked. “Last time I looked, it was $100,” the employee said. It’s not surprising that Amazon can make, pack, and ship me a tablet for just a bit more than the restocking fee on an iPad. But it’s not helping our growing e-waste problem.

Throwing ideas at the wall and shipping them

Amazon’s flotilla of always-listening Echo products is expanding rapidly. Review and tech sites are always a little skeptical, but they also link even the weirdest products, with affiliate codes, in part because Amazon saves its richest referral fees for its own products. (Full disclosure: we also add affiliate codes to our Amazon links, and if you buy these devices despite my efforts to talk you out of it, we may get a fee, too.)

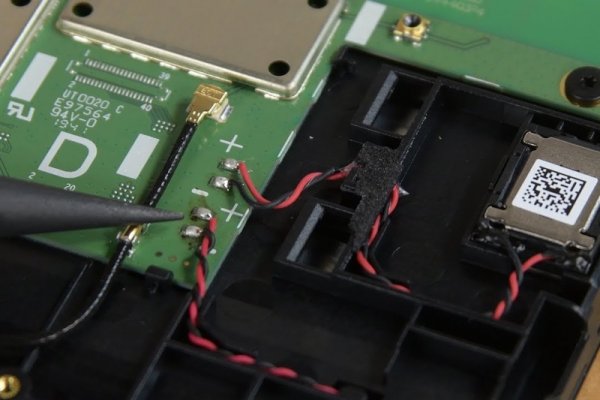

The Kindle parts that we sell are sourced from an electronics recycler because that is literally the only place we can find them. And those parts don’t exactly fly off the shelves. It’s hard to blame people for not wanting to fix or upgrade a tablet that often costs $35.

If the door handle on your Kenmore microwave breaks, you can probably get the part and repair instructions through Sears Parts Direct. If any part of your AmazonBasics Microwave (Works with Alexa!) breaks, you have to pray that someone dismantled one and put the parts on eBay. While an Amazon spokesperson emphasized that Amazon devices regularly receive updates that require no action on the owner’s part, we wonder how many years an Amazon microwave could expect to receive security updates, and whether customers could actually fix wayward software (we’ll update this post if we hear more).

Free, easy shipping for costly, tough waste

Amazon has a poorly advertised recycling program for its non-working electronics and trade-in offers for working devices (that mostly provide discounts on newer devices). I discovered these resources while writing this post, after more than 11 years writing about technology. Two of my friends with 15 years of combined experience in the field also did not know about them; the same goes for every iFixit staffer I asked.

At a basic web-search level, the Amazon recycling program is a kludgy form where you type in the raw number of Amazon devices you have in each category—e-readers, tablets, TV sticks, Dash buttons—and get a shipping label. There are also currently 10 U.S. locations where Amazon will accept discarded electronics.

Amazon claims that millions of devices have been saved by its refurbishment and trade-in programs. I’d wager most of those devices come from product returns rather than end-of-life trade-ins (we’ve asked Amazon to clarify this). Most people simply don’t know that Amazon will trade, refurbish, or recycle their stuff. As a result, the cost of recycling cheap products lands on local municipalities, most of them already overburdened with e-waste. But even if Amazon’s mail-in recycling were wildly successful, recycling should be the last resort for electronics. We should be making products that stand the test of time, and can have multiple owners.

Not all devices need to be top of the line, and buyers should have more options than a brand-new iPad. But it would be nice to see the realities of buying and recommending cheap devices acknowledged in product reviews. Even better, mention that there are many good markets for quality used and refurbished tablets and other devices out there: Apple and Samsung have refurbished offerings, or Swappa and Back Market provide nearly as much assurance at normalized prices. And for the deal hunters, Craigslist, OfferUp, and Facebook Marketplace are great local options.2

Activists like us pressure the makers of expensive, useful devices when they fail to design for reliability and a sensible afterlife. Sometimes it pays off. Apple is pushing the envelope and developing recycled sources for challenging materials like rare earth metals, and puts trade-in and recycling options in front of their customers. Microsoft redesigned the Surface Laptop 3 to dramatically improve its repairability. Amazon, meanwhile, is selling loads of electronic devices at artificially low prices, and their product responsibility policy is, at best, a quiet and very mixed message.

It’s high time that we demand better. Let’s hold Amazon to the same e-waste standards as the rest of the industry.

Note: This post has been updated to incorporate a statement from an Amazon spokesperson, and some of Amazons responses throughout.

Top image by 기태 김/Flickr

[1]: You can see why Amazon prefers relative comparisons to real numbers—stating the new Fire HD 10 is “30% faster” is a lot more impressive than “Now competitive with Samsung circa 2015.” ↩

[2]: Amazon does have its own secondary markets: “Renewed,” “Warehouse,” and “Certified Refurbished.” They’re not easy to differentiate or navigate, and their requirements for what counts as refurbished are less specific than many refurbished vendors. ↩

28 Comments

Great write-up! Thanks for bringing this up!

I’ve used their trade-in service once for a functioning and non-functioning device. Only found it when I was looking for ways to recycle Amazon products.

FYI : whime instead of whim

efrenr - Reply

This is fantastic. I never knew about the recycling program and have had an old, defunct Kindle hanging around the house. Now I know where to send it. Thank you!

Stephanie P - Reply

My Kindle Reader regularly reminds me that I can trade it in on a newer version.

Ed Reames - Reply

I’ve always wondered why the Amazon Fire tablets are such slow pieces of garbage.

Tom Parkison - Reply

The way to fix this MIGHT be to privilege repairable / recyclable products in tax policy. Amazon is a symptom. The cause is the consumer’s insistence on better for cheaper and the most efficient way to get there is to make the product functionally disposable and/or force the buyer back to the manufacturer to deal with problems.

We need to hard-wire some inefficiency into the marketplace.

S. Mittelstaedt - Reply