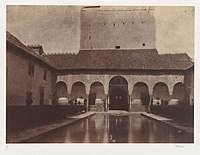

Court of the Myrtles

The Court of the Myrtles (Spanish: Patio de los Arrayanes) is the central part of the Comares Palace (Palacio de Comares) inside the Alhambra palace complex in Granada, Spain. It is located east of the Mexuar and west of the Palace of the Lions. It was begun by the Nasrid sultan Isma'il I in the early 14th century and significantly modified by his successors Yusuf I and Muhammad V later in the same century.[1] In addition to the Court of the Myrtles, the palace's most important element is Hall of Ambassadors (Spanish: Salón de los Embajadores), the sultan's throne hall and one of the most impressive chambers in the Alhambra.[2][3]

Names and etymology

[edit]Etymology of "Comares"

[edit]The name of the Palace, Comares, has led to various etymological research. For instance, Diego de Guadix wrote a dictionary about Arabic words in which it is said that Comares originally comes from cun and ari. The first term means "stand up" and the second one "look", in other words it would have meant "Stand up and look around" or possibly "Open your eyes and see", which is a way of referring the beauty of the place.[4] In the sixteenth century, a historian from Granada called Luis de Mármol Carvajal claimed that the term Comares derived from the word Comaraxía, which actually has a meaning related to a craftsmanship labor very appreciated by Muslims: a manufacturing technique of glass for exterior and ceilings.[5] A third suggested theory is that the name comes from the Arab word qumariyya or qamariyya. These ones designate the stained glasses that can be glimpsed from the Hall of the Ambassadors' balcony.[6] According to scholar James Dickie, another possibility is that Qumarish was the name of a region in the North of Africa where most craftsmen came from, in other words, the place might be called Comares in honour of the people who worked there.[7] Yet another suggestion is that it derives from an Arabic word relating to the Moon (Arabic: ﻗَﻤَﺮ, romanized: qamar), such as the adjective form qamarīyya.[2][8]

Names of the courtyard

[edit]The name of the Court of the Myrtles (Patio de los Arrayanes) is due to the myrtle bushes that surround the central pool.[9] Because of the pool, the courtyard is also called the Patio de la Alberca ('Courtyard of the Pool').[10] It is sometimes also called the Patio de Comares ('Comares Court').[11]

History

[edit]The Alhambra was a palace complex and citadel begun in 1238 by Muhammad I Ibn al-Ahmar, the founder of the Nasrid dynasty that ruled the Emirate of Granada.[12] Several palaces were built and expanded by his successors Muhammad II (r. 1273–1302) and Muhammad III (r. 1302–1309).[13] In 1314 Isma'il I came to the throne and undertook many further works in the Alhambra. His reign marked the beginning of the "classical" period or high point of Nasrid architecture.[14][15] Isma'il decided to build a new palace complex to serve as the official palace of the sultan and the state, known as the Qaṣr al-Sultan or Dār al-Mulk.[14] The core of this complex was the Comares Palace, while another wing of the palace, the Mexuar, extended to the west.[16] On the east side the Comares Baths, a royal hammam, were also built. The baths are probably the section that is best-preserved from Isma'il I's time, as the rest of the complex was significantly modified and refurbished by his successors.[17]

Yusuf I (r. 1333–1354) expanded the palace, most notably building the Comares Tower and the Hall of the Ambassadors (the throne hall) on the north side of the Court of the Myrtles; prior to this, a smaller lookout room or mirador may have existed on this side, similar to earlier palaces like the Partal Palace or the Generalife.[2] He also built or converted existing towers along the northern walls of the Alhambra to serve new purposes, such as the Torre de Machuca in the Mexuar and the Torre de la Cautiva in another area further east.[13] Under Muhammad V (r. 1354–1359 and 1362–1391) Nasrid architecture reached its apogee, which is evident in the nearby Palace of the Lions which he built to the east of the Comares Palace.[18] Between 1362 and 1365, he rebuilt or refurbished the Mexuar and between 1362 and 1367 he refurbished the Comares Palace (namely the Court of the Myrtles and the Hall of Ambassadors).[13] The Comares Façade on the south side of the Patio de Cuarto Dorado ('Courtyard of the Gilded Room') is dated to 1370 during his reign.[19] Thus, the Comares Palace's current appearance and decoration was finalized by Muhammad V, whose name is mentioned in many surviving inscriptions inside.[13]

After the 1492 conquest of Granada by the Catholic Monarchs, the Alhambra was converted into a royal palace of Christian Spain. Significant modifications were carried out in the Mexuar and in the environment around the Comares Palace.[20][1] The Catholic Monarchs linked the Comares Palace and the Palace of the Lions together for the first time.[21] The Spanish monarchs also knew the significance of the Comares Tower in the complex and when they visited the Alhambra the royal flag was flown from this tower instead of the Torre de la Vela in the Alcazaba.[22] In the 16th century, some southern parts of the Comares Palace were demolished to make way for the new Renaissance-style Palace of Charles V.[20][23]

In the 19th century Rafael Contreras undertook many restorations across the Alhambra palace complex, sometimes adding his own modifications. In the Comares Palace he added crenelated turrets above the east and west ends of the Sala de la Barca (on the north side of the Court of the Myrtles) and also repainted the Comares Baths in garish colours that are likely inaccurate.[24][7] In 1890, a fire severely damaged the Sala de la Barca, resulting in the loss of its wooden ceiling. The ceiling was later reconstructed with the help of surviving fragments and finished in 1965.[3]

Description of the Comares Palace

[edit]General layout

[edit]The Comares Palace is centered around the Court of the Myrtles, with the Comares Tower and the Hall of Ambassadors to the north and a southern pavilion or structure that was mostly demolished to make way for the Palace of Charles V to the south. The Comares Palace is contiguous with the Mexuar complex to the west, to which it was always connected and with which it formed one large complex. It was originally independent of the Palace of the Lions to the east, but is now connected to it via a small passage. A royal baths complex, the Comares Baths, is annexed to the palace on the east side.[1][20]

1) Comares Façade, 2) Sala de la Barca, 3) Hall of Ambassadors, 4) Changing room of the baths, 5) Cold room of the baths, 6) Warm room of the baths, 7) Hot room of the baths

Comares Façade and access to the palace

[edit]

The Court of the Myrtles was entered from the west via a smaller courtyard, the Patio del Cuarto Dorado ('Courtyard of the Gilded Room'), at the east end of the Mexuar. The Patio de Cuarto Dorado is known for a monumental, richly-decorated southern façade that has been interpreted as the "façade" of the Comares Palace and is known as the Comares Façade or Façade of the Comares Palace.[19][25][26][27] This façade dates from the time of Muhammad V.[13] It has two identical doors, with the left (eastern) door leading via a winding passage to the Court of the Myrtles and the right door leading to other private chambers, possibly a treasury, attached to the Mexuar.[28][19]

The façade is one of the most heavily-decorated walls in the Alhambra, covered in stucco decoration for most of its surface except for tile decoration along the lower portions (some of which comes from modern restorations).[19] The carved stucco includes an Arabic inscription featuring a poem by Ibn Zamrak (d. 1393) and the Throne Verse of the Qur'an (2:255), which may indicate that this area was sometimes used by the sultan to hold audiences or other ceremonies.[27][19] Above the doors are two double-arched windows and one single-arched window between them. Above these is a muqarnas ("stalactite"-like) cornice that precedes a wide wooden eave, which in turn would have sheltered the seat of the sultan at the top of the courtyard steps.[27][29]

Court of the Myrtles

[edit]

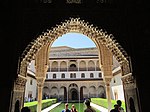

The Court of the Myrtles measures 23 to 23.5 metres wide and 36.6 metres long, with its long axis aligned roughly north-to-south.[23] At the middle, aligned with the axis of the court, is a wide reflective pool. The pool measures 34 metres long and 7,10 meters wide.[30] The myrtle bushes that are the court's namesake grow in hedges along either side of this pool. Two circular floor fountains are located at either end of the pool. The water from each fountain runs along a short channel towards the pool, but the channel is design to let the water slow and pause before emptying into the pool, thus reducing the formation of ripples and preserving the water's still surface. The effect of the water reflecting sunlight during the day as well as the image of the architecture around it is a crucial part of the aesthetic effect of this space.[31] Elongated rectangular courtyards with a central water basin were already an established feature of Nasrid architecture that is evident in older palaces of the Alhambra, in particular the Palacio del Partal Alto.[23]

At the south and north ends of the courtyard are ornate porticos consisting of a wide central arch flanked by three smaller arches on either side. The arches are richly decorated with stucco sculpted in arabesque (vegetal), sebka, and epigraphic motifs. This decoration, like that of the halls behind them, dates from the time of Muhammad V, probably between 1362 and 1367.[23] The gallery spaces behind the porticos are flanked at their east and west ends by decorative niches covered with muqarnas vaulting.[23]

Behind each portico is a set of halls. The southern halls or "southern pavilion" were largely demolished during the construction of the adjacent Palace of Charles V in the 16th century. Only the façade of this structure was preserved in order to maintain the visual integrity of the courtyard.[32][23] The doors on the sides of the Court of the Myrtles lead to four rooms that probably served as living spaces, while other doors lead to passages to and from the Patio de Cuarto Dorado to the west and the Comares Baths (the hammam) to the east.[33] A passage also now leads to the Palace of the Lions, but during the Nasrid period these two palaces were completely independent of each other. They were only connected together after the 1492 conquest, when the Catholic Monarchs moved in.[21]

- Details of the Court of the Myrtles

-

Court of the Myrtles, looking towards the southern façade

-

One of the lateral façades of the courtyard, looking east

-

The northern portico of the courtyard

-

One of the lateral niches in the northern gallery, with muqarnas sculpting and zellij tiling inside

-

Frieze of stucco decoration in the galleries, with tile decoration below

Sala de la Barca

[edit]Behind the northern portico of the courtyard is a muqarnas-decorated archway that leads to the Sala de la Barca, a wide rectangular hall with an ornate vaulted wood ceiling and alcoves at its east and west ends. The ceiling has a rounded profile and is covered in geometric motifs. The alcoves at either end are separated from the rest of the hall by round arches embellished with muqarnas spandrels transitioning to the wooden vault.[34] The original ceiling was destroyed by fire in 1890, but with the help of surviving fragments it was later meticulously reconstructed, a process that was completed in 1965.[3] A popular etymology alleges that the name Barca comes from the Spanish word for "boat", referring to the shape of the ceiling. Most scholars, however, accept that the name is probably instead derived from the Arabic word baraka, meaning "blessing", which is included in the Arabic inscriptions around the hall.[23][35][36][37]

Some scholars, such as James Dickie, have suggested that the hall was the bedroom and summer apartment of the sultan.[36][27] Robert Irwin argues that this is unlikely, given the room's location at the entrance of an audience chamber (the Hall of the Ambassadors).[38] The official guidebook of the Alhambra, published by the Patronato (official agency in charge of the site's preservation), calls the hall an "antechamber" to the Hall of the Ambassadors, though the side alcoves of the hall may have held beds.[35] It may have also been a sitting room or waiting room.[34] A doorway in the corner of the western alcove gives access to a small winding passage that leads to a preserved latrine chamber.[3][7]

- Sala de la Barca

-

Entrance archway of the Sala de la Barca (looking south back towards the courtyard)

-

The Sala de la Barca, looking east across the hall

-

Ceiling of the hall: a rounded wooden vault, transitioning through muqarnas to the arch of the side alcove

Hall of Ambassadors

[edit]

The Sala de la Barca leads in turn to the Hall of Ambassadors (Salón de los Embajadores), also known as the Salón de Comares ('Comares Hall') or Salón del Trono ('Throne Hall'). This hall is entered by passing through two consecutive ornate archways aligned with the entrance to the Sala de la Barca.[3] The narrow space between the two archways is occupied on the right (eastern) side by a small oratory or prayer room with a preserved mihrab, while the left (western) space leads to a staircase that grants access to more rooms upstairs, probably the sultan's winter apartments.[27][36] The jambs (sides) of the last archway upon entering the Hall of Ambassadors are pierced with two small and decorated arched niches. This type of niche was called a taqa in Arabic and was probably used to store either a decorative vase or a jug of water to drink.[39][40]

The Hall of the Ambassadors is contained within the massive Comares Tower. The tower is about 16 meters wide, has a total height of 45 meters, and its walls are about 2 to 3 meters thick.[41][2] The hall is the largest and most impressive in the Alhambra, as well as one of the largest interior spaces of any historic palace in the western Islamic world (the Maghreb and al-Andalus).[2][42] It has a square shape measuring 11.3 meters per side and it rises to a height of 18.2 metres.[2] It served as a throne hall and audience chamber.[40]

The walls of the hall are covered in detailed stucco decoration and with mosaic tile decoration (zellij) along the lower walls. The decoration includes arabesque, geometric, and epigraphic motifs which were originally painted with bright colours.[27] Among the inscriptions are Qur'anic verses and poems. Three of the walls are pierced at ground level by three alcoves with windows. The middle alcove in each of the walls has a double window split by a column, while the other two side alcoves have a single-arched window.[23] The central alcove in the back wall is more skillfully decorated than the rest and is where the sultan was seated, framed by the double-arched window behind him.[43][27] Wall inscriptions around this particular alcove feature a poem by either Ibn al-Jayyab (d. 1349) or Ibn al-Khatib (d. 1374) which alludes to the sultan's throne.[27] At the top of the walls, just below the dome ceiling, is a line of small windows with grilles forming a geometric latticework. The latticework of both sets of windows above and below were probably originally filled with coloured glass, but this has been lost, probably due to the explosion of a nearby gunpowder magazine in 1590.[44][45]

One of the most unusual decorative features of the hall was the floor, which is paved with lustre tiles. The entire floor may have originally been paved like this but only the center of the room has preserved the tiles. Not all of the present tiles are original, as many are reused tiles that were moved here in the 16th century. The original tiles bear the inscription "wa la ghaliba illa-llah" (Arabic: ولا غالب إلا الله, lit. 'And there is no conqueror but God'), a Nasrid motto.[46][47][48] The presence of an inscription containing the name of God (Allah) is unusual, as it is assumed that a pious Muslim would never step foot on the name of God.[46] James Dickie suggests that visitors would have avoided stepping on these tiles.[47]

The elaborate wooden dome ceiling has a surface area of approximately 125 square metres, making it the largest wooden construction of its kind in the western Islamic world.[2] The ceiling has a complex geometric pattern formed by 8017 interlinking pieces of wood nailed and stacked with each other, which has been interpreted as a representation of the seven heavens.[44][45][27] The motif is composed primarily of a repeating twelve-sided star pattern that was originally enhanced with painted colours, although the colours have since faded.[45] Right below the base of the dome is an inscription featuring surah 67 (al-Mulk) of the Qur'an, which describes God as the "Lord of Heavens". Scholars have interpreted this as an indication of the ceiling's symbolic meaning, supporting the hypothesis that it is a celestial representation.[49][47][2][43][27]

- Elements of the Hall of Ambassadors

-

Archways at the entrance of the Hall of Ambassadors. The wall of the arch on the right contains a taqa niche

-

The small oratory located between the walls of the two archways at the entrance to the hall (on the east side). A mihrab is visible inside.

-

Doorway for the staircase to the upper floor, located between the walls of the two archways at the entrance to the hall (on the west side)

-

View towards the north side of the Hall of Ambassadors, with windows at ground level and smaller windows just below the dome

-

View of the south side of the hall, looking towards the entrance

-

The central alcove at the back of the hall, where the sultan's throne was positioned

-

Tile decoration (zellij) along the lower walls

-

Stucco decoration on the walls, including epigraphic motifs (Arabic inscriptions), a sebka motif, and arabesques

Comares Baths

[edit]The royal hammam of the palace, the Comares Baths, is one of the largest and best-preserved hammams built on the Iberian Peninsula.[1][50] Although dating to the time of Isma'il I, Yusuf I probably also refurbished or modified some of it.[1][51] Because of the exceptional state of preservation, the baths are not normally accessible to tourists today, in order to protect them.[50] Like other Islamic hammams, it follows the general principles and components of Roman baths. A changing room or resting room, the bayt al-maslak͟h (its Arabic name), corresponds to the Roman apodyterium. It is also known in Spanish as the Sala de las Camas ('Hall of the Beds'). This is the most impressive room in the complex, preserving almost all of its original elements including its tile and stucco decoration, its flooring, and a fountain.[52] An inscription on its upper level suggests that it may have been given its final form by Muhammad V, perhaps around the same time that the nearby Palace of the Lions was being built.[53] It is shaped like a small square courtyard with four columns upholding an upper-level gallery. Two iwans or enclosed side rooms are located on the west and east sides of the hall, separated from the main space by a double arch. The central space is covered by a square lantern ceiling of wood, which provides illumination and ventilation.[52][53] The decoration includes two poems by Ibn al-Jayyab.[53] The painted colours of the decoration, however, date from an 1866 restoration by Rafael Contreras, when the ceiling and other elements were also repaired.[51][54]

After the bayt al-maslak͟h are three rooms with vaulted brick ceilings pierced by star-shaped openings. The first room is the bayt al-barid (cold room), which contains a fountain. The second is the bayt al-wastani (middle room or warm room), which is the largest of the steam rooms and is divided into three "naves" by two sets of arches, with the central space being much larger than the two side spaces. The last room is the bayt al-sak͟hun (hot room), which has two wall niches containing fountains that provided cold and hot water. Behind the hot room was a service room containing a furnace that burned wood to heat water in a boiler which produced steam. The hot steam was channeled through a hypocaust system: a network of clay pipes that runs under the floors to heat the rooms. Some of the tiles in the steam rooms were replaced in the 16th century and feature the imperial motto of Charles V and his dynasty, "Plus Ultra".[52][53]

- Comares Baths

-

The Sala de las Camas (or bayt al-maslak͟h), the changing room of the Comares Baths (photo from late 19th century)

-

Upper level and decoration of the changing room

-

The warm room (bayt al-wastani)

-

Fountain in the side wall of the hot room (bayt al-sak͟hun)

Notes

[edit]- ^ This image is based on an 1892 floor plan. Many restorations and archaeological excavations were carried out after this time. While the plan of the Comares Palace is essentially unchanged, the remains of the Mexuar that are visible today are not fully shown on this plan.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Arnold 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Arnold 2017, p. 266.

- ^ a b c d e López 2011, p. 116.

- ^ Guadix 2005: p. 551

- ^ Pijoán 1954: p. 516

- ^ Irwin 2003: p. 36 Cfr: Sánchez Mármol, in his book Andalucía Monumental (Granada 1985)

- ^ a b c Dickie 1992, p. 140.

- ^ Irwin 2004, p. 28.

- ^ "The court of the myrtles". Patronato de la Alhambra y Generalife. Retrieved 2022-02-17.

- ^ López 2011, p. 112.

- ^ Dickie 1992, p. 135.

- ^ García-Arenal, Mercedes (2014). "Granada". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Three. Brill. ISSN 1873-9830.

- ^ a b c d e Arnold 2017, p. 236-268.

- ^ a b Arnold 2017, p. 261.

- ^ López 2011, p. 295.

- ^ Arnold 2017, p. 236-238.

- ^ Arnold 2017, p. 236.

- ^ Bloom 2020, p. 164.

- ^ a b c d e López 2011, p. 109.

- ^ a b c López 2011.

- ^ a b Irwin 2004, p. 47.

- ^ López 2011, p. 120.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Arnold 2017, p. 265.

- ^ Irwin 2004, p. 31, 37, 41, 47.

- ^ Irwin 2004, p. 34.

- ^ Dickie 1992, p. 137.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Bloom 2020, p. 159.

- ^ Arnold 2017, p. 273.

- ^ Dickie 1992, p. 138.

- ^ "Court of the Myrtles". Alhambra de Granada.

- ^ López 2011, p. 112-115.

- ^ López 2011, p. 120-123.

- ^ López 2011, p. 115, 123.

- ^ a b M. Bloom, Jonathan; S. Blair, Sheila, eds. (2009). "Granada". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ a b López 2011, p. 115-116.

- ^ a b c Dickie 1992, p. 139-140.

- ^ Irwin 2004, p. 41-42.

- ^ Irwin 2004, p. 42.

- ^ López 2011, p. 115.

- ^ a b Irwin 2004, p. 43.

- ^ Ruiz Souza, Juan Carlos (2020). "Granada and Castile in the Shared Context of the Islamic Art in the Late Medieval Mediterranean". In Cobaleda, María Marcos (ed.). Artistic and Cultural Dialogues in the Late Medieval Mediterranean. Springer Nature. p. 129. ISBN 978-3-030-53366-3.

- ^ López 2011, p. 110, 116.

- ^ a b López 2011, p. 118.

- ^ a b López 2011, p. 119-120.

- ^ a b c Irwin 2004, p. 44.

- ^ a b Irwin 2004, p. 4445.

- ^ a b c Dickie 1992, p. 139.

- ^ López 2011, p. 119.

- ^ Irwin 2004, p. 43-44.

- ^ a b López 2011, p. 123.

- ^ a b Dickie 1992, p. 141.

- ^ a b c López 2011, p. 123-127.

- ^ a b c d Arnold 2017, p. 268.

- ^ López 2011, p. 124.

Bibliography

[edit]- Arnold, Felix (2017). Islamic Palace Architecture in the Western Mediterranean: A History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190624552.

- Bloom, Jonathan M. (2020). Architecture of the Islamic West: North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula, 700-1800. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300218701.

- Dickie, James (1992). "The Palaces of the Alhambra". In Dodds, Jerrilynn D. (ed.). Al-Andalus: The Art of Islamic Spain. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 135–151. ISBN 0870996371.

- Irwin, Robert (2004). The Alhambra. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Irwin, Robert (2010). La Alhambra. Granada: Almed. ISBN 978-84-15063-03-2.

- López, Jesús Bermúdez (2011). The Alhambra and the Generalife: Official Guide. TF Editores. pp. 110–127. ISBN 9788492441129.

- Pijoán, José (1954). Historia general del arte, Volume XII, Summa Artis collection. Islamic Art. Madrid: Espasa Calpe.

- de Guadix, Diego (2005). Compilation of some Arabic names that the Arabs put to some cities and many other things. Edition, introduction, notes and index: Elena Bajo Pérez y Felipe Maíllo Salgado. TREA Editions. ISBN 84-9704-211-5.